"'The 94-year-old O’Neil was admitted to a hospital Saturday after complaining that he didn’t feel well,' said Bob Kendrick, a friend who also is marketing director for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. ‘Mostly the doctors just wanted to be extra cautious with him,’ Kendrick said Monday. ‘They just wanted to slow him down a little.’”

Many modern baseball fans got to know O’Neil when he served as one of the prime story-tellers in Ken Burns’ splendid PBS documentary “Baseball” in 1994. His warm personality and yarn-spinning talent has made him a favorite with millions of fans who never saw him play baseball for the Kansas City Monarchs.

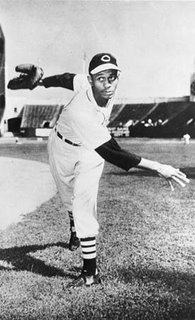

Satchel Paige, circa 1949

Satchel Paige, circa 1949 When I think of O’Neil, it isn’t long before my remembrance of Leroy “Satchel” Paige (1906-82) flickers onto the screen in my head. I can see him on the mound at Parker Field, with his windmill windup, then that high kick and smooth release. Long after his days as the best pitcher in the Negro Leagues, following his years in the American League, Paige was on the roster of the Miami Marlins (1956-58), of the International League. So, too, were the Richmond Virginians, or V's, for short.

When I saw him Paige was in his early-50s, maybe a little more, as his age was always somewhat disputed. Not a starter, anymore, he worked out of the bullpen. The boos would start as soon as some in the crowd noticed his 6-3, 180-pound frame warming up in the middle of a game. When he’d be called in to pitch in relief, the noise level would soar. White men were booing with practiced passion. Not all the white men booed, but many did, especially the old ones. And, as children will do, a lot of the white kids broke the other way, to cheer.

In 1971 Paige was the first of the Negro Leagues’ stars to be admitted to Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame, based mostly on his contributions before he helped break the Major League color line. The statistics from his pre-Big League days are mind-boggling. Some say he won about 2,000 games and threw maybe 45 no-hitters. Sometimes, he'd pitch every game in a week's schedule.

Yet, for many white adults in Richmond -- 50 years ago -- then caught up by the thinking that buoyed Massive Resistance, any prominent black person was seen as someone to be against. So, they might have booed Nat King Cole or Duke Ellington, too. But Paige was more than a star athlete, he was a first class showman. Long before the impish poet/boxer Muhammad Ali, there was the playful Satchel Paige, with his famous six guidelines to success:

- Avoid fried meats that angry up the blood.

- If your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts.

- Keep the juices flowing by jangling gently as you walk.

- Go very lightly on the vices, such as carrying-on in society - the society ramble ain't restful.

- Avoid running at all times.

- Don't look back, something may be gaining on you.

“Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige was a legendary storyteller and one of the most entertaining pitchers in baseball history. A tall, lanky fireballer, he was arguably the Negro leagues’ hardest thrower, most colorful character and greatest gate attraction. In the 1930s, the well-traveled pitcher barnstormed around the continent, baffling hitters with creatively named pitches such as the Bat Dodger and Hesitation Pitch. In 1948 he was sold to Cleveland on his 42nd birthday, becoming the oldest player to make his major league debut, while helping the Indians win the pennant.”

So, in 1957, Paige would take forever to walk from the bullpen to the mound. Then each of his warm-up pitches would be a big production, with various slow-motion-like full windups. Once he was ready, when the batter dug in, the first thrown ball from Paige whistled toward home plate with blinding speed for a strike, every time, and the kids went nuts again.

At the time I hadn’t the slightest idea that what I was seeing was an aspect of the changes the South was going through, then, to do with race. Like most of the other boys, I mostly got a kick out of seeing Paige piss off all those old goats who couldn’t stand him. It was fun. Plus, I instinctively liked Paige, he was naturally cool.

Paige, of course, knew very well he was in the South. Being from Mobile, Alabama, he knew what was going on. He was a consummate performer, who knew there wasn’t much he could do to change the boos. So, he good-naturedly played to the cheers, just as he always had.

Instead of looking back, now I know Satchel Paige was seeing the future.

Images: satchelpage.com

No comments:

Post a Comment