Fiction by F.T. Rea

Fiction by F.T. Rea

September 21, 1977: The Luis Bunuel double feature playing at the Fan City Cinema drew a sparse but appreciative crowd. In the lobby, just before the nine-thirty show got underway, manager Roscoe Swift said to a pair of regular customers who were Bunuel aficionados, “Yeah, I suppose if we’ve got to go broke at least we’re doing it with style.”

At 10:45 p.m. Swift locked the bank deposit from the evening’s take in the ancient safe in his office. As he left the theater the 29-year-old manager set out to wash away the still-clinging vestiges of a hangover that had dogged him all day. Swift’s destination was the stained glass and wood-paneled confines of J.W. Rayle, his favorite watering hole. Once outside, he decided to walk, hoping the fresh air would do him some good.

Monroe Park was quiet. As he walked Roscoe recollected a series of images from events that had unfolded in that park, which bordered the Virginia Commonwealth University academic campus. The montage stopped abruptly at his memory of a Sunday afternoon live-music happening where a young man fell to his death from atop the park’s cast iron fountain.

Upon arriving at the restaurant Roscoe was glad to see Rusty Donovan was the bartender on duty. He and Rusty had been friends since boot camp in 1966. Eleven years later they were teammates on the J.W. Rayle softball team.

Lean and agile Rusty was the best all-around athlete in his high school class. Yet he passed on opportunities to play college basketball because he didn’t crave competition as do many jocks. Nor did he have any desire to launch a serious career. He liked being a bartender, attracting pretty girls and playing shortstop on the bar’s softball team. All three tasks were easy for Rusty. That’s how he liked it.

Rusty’s droopy mustache widened as he glanced up from washing a glass to see Roscoe. “Yo!”

“Heineken please,” Roscoe said, taking a seat at the bar. “Slow night?”

“So far,” Rusty replied, setting the bottle in front of Roscoe, “Maybe it’ll pick up. Peach said she’d stop by. Sal just called, he’s on his way.”

“It was slow at the Fancy, too,” said Roscoe. “I watched most of ‘Los Olvidados,’ it still knocks me out. Bunuel is the champ.”

“Aw, give me the ol‘ ‘Dog,’ every time,” Rusty laughed. “That eyeball-slicing scene, oh man, the effect it ... it’s cosmic.”

“The audience always groans,” Roscoe affirmed. “What year was it that kid died climbing on the fountain in Monroe Park?”

“Beats me,” Rusty shrugged. “You’re the stickler for dates. I’d guess five or six years ago, maybe more. Why?”

“No real reason,” said Roscoe, “I walked here from the Fancy and something reminded me of being there the afternoon it happened. I didn’t see him fall, but I remember Bake said he was rocking back and forth. I think you and Finn were there, too. I sure remember how the fountain looked, all skewed.”

Rusty asked, “Didn’t that happen the day after we went to that post-Kent State war-protest in DeeCee?

“Sounds right,” said Roscoe. “Kent State was 1970, so...”

“Look!” bellowed an unfamiliar male voice behind Roscoe, “I saw you. Don’t lie!”

Rusty cringed. Roscoe turned to look behind him at the squabbling couple, seated about twelve feet away.

The balding, rather soft-looking man, was probably in his mid-30s. Roscoe pegged him as the ne’er-do-well son of a fat cat. Decked out in a big-collared shiny polyester get-up, the guy had an air about him that reeked of bad karma. His opposite at the small round lounge table was a striking beauty. She couldn’t have been much over 21, if that. With her dark hair and gamine, long-limbed look, Roscoe was reminded of Audrey Hepburn, as she appeared in “Sabrina.”

After taking a generous swig of his beer, Roscoe was pleased to see the veteran bartender cranking the volume up on the bar’s stereo, which was playing a reel-to-reel tape: The rather apt song of the moment was the Amazing Rhythm Aces’ “Third Rate Romance.”

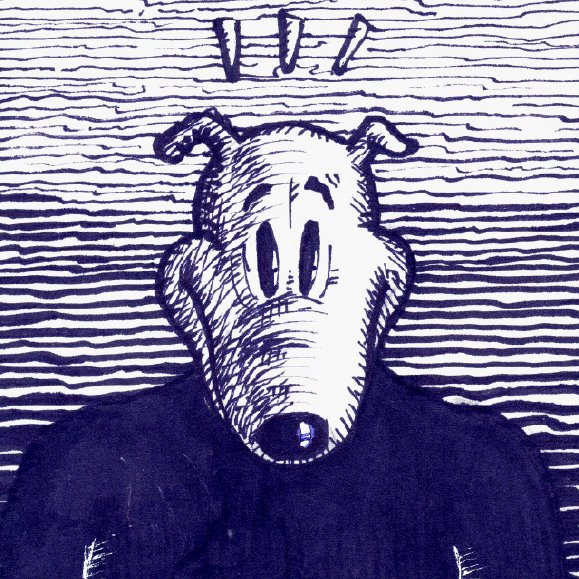

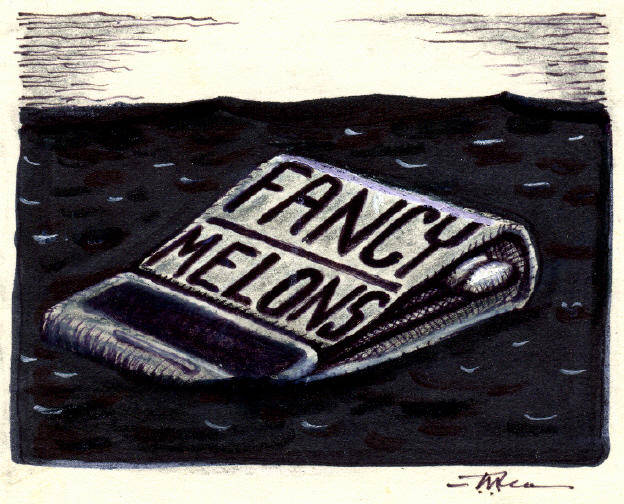

Roscoe cracked his knuckles as he once again noticed the irritating joke reproduction of the Mona Lisa on the back wall; this version of Mona was cross-eyed. Once again, he wondered why the silly thing struck others as funny.

A couple of minutes later the song ended and Roscoe glanced at the bickering girl. She was sitting alone, retouching her lipstick. He studied her gypsy-like eyes, her long nose and wide mouth. Her small head rested perfectly on a swan-like neck. She had a dark tan. Wearing a form-fitting powder blue tube top and tiny floral-print shorts she looked like a fancy dessert.

Leaning on her elbow, lovely Sabrina glanced up from her hand mirror at Roscoe. Her vexed expression melted into a sweet smile that took his breath away. When had he seen her before? After a long second, the girl averted her eyes, unsmiled, and nervously lit up a cigarette. Roscoe turned away, so as not to stare.

His thoughts drifted. Over the previous Labor Day weekend Roscoe and his wife of nearly seven years, Julie, decided to separate, temporarily. He wondered if the hard-edged single man’s life he had been leading would bring tobacco back into the picture. It had been almost a year since he had fired up a Kool Filter.

“Do you believe that?” whispered Rusty, nodding toward the two-top, as Sabrina’s sparring partner returned. “Why would she be with him?”

“What a waste,” agreed Roscoe, polishing off the dregs of his first beer of the night. He closed his eyes to see the teal color of Julie’s eyes light up and dissolve into a familiar picture of her in mid-stride, running on the beach the day her met her.

Rusty placed a second frosty green Heineken in front of his friend and said, “On the house, amigo.”

“Just what the doctor ordered,” said Roscoe, “thanks.”

Sal Modiano, the art professor, walked into the room. Sal was a skinny, cocky son of Italian immigrants from New Jersey, he looked like a character straight out of “The Godfather.” Sal was an ordinary athlete, if that. He played second base on the restaurant’s softball team.

Since the split-up with Julie, Roscoe had been staying in Sal’s Grove Avenue carriage house art studio. The amenities were minimal but the roof didn’t leak. Although he had no plan for what to do next, after only two weeks, Roscoe already sensed that he and Julie would not live together again. While they still cared for one another, far too many injuries to their relationship -- which began the summer before they were juniors in high school -- had been ignored over time, left to heal wrong.

As John Lennon’s voice warbled from the speakers, Roscoe softly sang along, “Ah, bowakawa pousse, pousse.”

“Yeah, yeah ... Turn me on dead-man,” Sal chuckled, as he plopped down next to Roscoe at the bar. “Rustman, I’ll have the same as our leftfielder here. And, ‘Scoe, what the hell does that bozo-cow-eye, pussy, pussy line actually mean?”

“Beats me,” Rusty laughed.

Roscoe shrugged, then suggested to Sal they move from the bar to get further away from the obnoxious battle underway behind them. Sal nodded and picked up his beer to follow Roscoe to a table nearer the back of the room.

Having scored an ounce of expensive hothouse marijuana that afternoon, Sal was wearing a telltale illegal smile. “Bet your life, man, I’m having just an excellent night -- happy hour at the Rainbow Inn, followed by some excellent oysters at Gatsby’s...”

“Who was at the Rainbow?” asked Roscoe.

“The usual suspects,” said Sal. “Zach came in. The mouthpiece bought a round for the house to celebrate winning a big case. Later on JD was in the back booth dealing nasty, nasty half-grams for thirty-five bucks. The sample line felt like he had cut it with Ajax. I think JD, the crazy deejay, is stepping all over the product and going to get himself in trouble. Oh, and Julie came in.”

Roscoe resisted, then asked, “Was she with anybody?”

“One of her girlfriends,” Sal replied. “I forget, ah, heavy jugs, thick ankles, bleached blonde hair. What say we take us a little a ride ‘round the block to burn one? I’ve got a fresh batch of sweet primo for you to test. Forget Julie for a while, man. Give it a rest.”

*

Twenty minutes later, the teammates were finished with their smoke break. Re-entering Rayle’s lounge, Roscoe and Sal were pleasantly surprised to see that Rusty’s sharp-looking new strawberry blonde girlfriend, Peach, was sitting at the bar with another young woman, an equally attractive brunette.

Peach introduced Kit to Roscoe. Sal already knew her, as both girls were art majors who had transferred from Old Dominion University. Both wore the obligatory paint-speckled faded blue jeans and T-shirts that signaled they were art girls.

Peach mentioned that Kit had played volleyball at ODU. Roscoe liked her immediately. He hoped to get to know her better, but when the battling couple resumed their argument, he and Sal fled to their table.

For Roscoe and Sal a discussion followed that digressed effortlessly from the rudderless aspect of current politics into the days of the Grove Avenue Republic, which was a group of anarchy-loving neighbors living on the 1100 block of Grove. That area of the Fan District was the epicenter of a few notable street parties that brought out the worst in the local police force. Roscoe brought up the time the cops actually turned dogs loose to chew up a crowd of hippies.

Sal complained about how the Fan, with its distinctive architecture, was suddenly losing its front porches to a “weird trend” in renovation.

“What’s so wrong about a porch?” demanded Sal, in a voice the whole room could hear. “The Fan is changing, man! No surprise, Bake was right again when he predicted a new breed would move into the Fan to run off the hippies and old folks. Look around, it’s happening!”

“Yep, the times are a-changing,” said Roscoe. “How about having to choose between Disco and Punk Rock?”

“Not in Rayle, not on my shift,” Rusty tossed out from behind the bar. On cue, the next cut on the tape started -- “Poor Little Fool,” by Ricky Nelson.

Sal’s rant morphed into his favorite source of material for yarn-spinning, the colorful life of the late Roland “Bake” Baker.

A bullet to the head finished off Bake in 1975. His body was found in a boarded-up house on Floyd Avenue, a couple of blocks from where Julie and Roscoe lived. It had never been determined what happened, or who else was involved. The weapon that killed him wasn’t found. In the newspaper, according to a police department spokesperson, it was considered to have been, “a drug-related murder.” In the same article, Bake was made out to have been a “known associate of anti-American radicals and underworld figures.”

While Bake had played guitar in a couple of Rock ‘n’ Roll bands and dealt pot on a substantial basis for several years, to cast him as a spy or mobster was preposterous to anyone who knew him at all.

For the benefit of those in the room who were tired of hearing the unhappy couple slug it out, Sal, in full Jersey throat, began telling the “Bake Calling His Shot” story. Roscoe and Rusty had heard it many times.

According to Sal, it all happened at Finn Daley’s pad on Harvie Street. There were six guys there. The happy raconteur named them all to add credibility to the tale.

“They were discussing the clues to the Paul-is-dead controversy, or scam,” said Sal. “Bake was stretched out on his back on the couch. His feet were on the coffee table, next to several beer cans, an ashtray, a bong, and a Coca-Cola bottle. Abruptly, the late Mr. Baker announced, ‘Watch this shot, boys. Swish!’”

Sal took up a matchbook and began acting out the part. “He pulled the last match out and whistled. Then he aimed it, man, squinting one eye. He tossed it at the bottle, and ladies and gents, the match went straight into the Coke bottle like a guided missile. Voila!”

“Voila?” Roscoe interrupted, “Did it swish?”

“‘Voila,’ is what he said,” Sal fired back. “You remember, Rusty, we measured the flight of the match at over seven feet. That’s a one-in-a-hundred, a one-a-thousand shot, man. He called it. Calling the shot man, that’s…”

“How do you know Bake was aiming for the Coke bottle?” Roscoe inquired. “What makes you think you even know what he meant? He could...”

Sal puffed up. “I believe you were still in the brig then, man. I was there and heard him call the shot. I saw the match go in the bottle.”

Roscoe laughed, “Yeah, I know. Oh, for the record, by then I out of the Navy and in school. I was at class that day.”

It both amused and annoyed Roscoe that so many of Bake’s old running mates were continuing to glorify everything he had ever done. Bake climbed the WTVR broadcast tower. Bake hit a flamboyant politician, Howard Carwile, with a water balloon. Got away with it. When the riot broke out in the midst of the Cherry Blossom Festival, he torched one, maybe two of the police cars. Got away with it then, too. Stranger than the exaggerations of Bake’s actual doings were the ghost rumors and soap opera speculations concerning his demise. Roscoe was uncomfortable with the idea of Bake, who had been his closest friend, becoming a minor league James Dean-like cult figure.

“Knowing Bake,” said Roscoe, as Dan Hicks’ “I Scare Myself” began to fill up the room with close harmony. “I just wonder if he had a vision of the match going into the bottle. Or, if he thought he could will it to do so. No doubt, he was capable of either...”

A glass broke on the floor. Sabrina stood up and stomped her foot. Tearful and angry, she raised her voice, “...and don’t ever follow me again!” Her outraged companion grabbed her arm, forcefully. He hissed something unintelligible.

Roscoe closed his eyes and reminded himself that it was none of his business. Sal glanced sideways at the imbroglio and said, “Damn it, man, I wish he wouldn’t rough her up like that.”

“This is awful!” said Roscoe, turning to look through the antique leaded glass windows at the misty night on Pine Street.

“Ease up, buddy,” commanded Rusty from behind the bar, in a tone unusually stern for him.

The angry girl tried to wrench herself loose from the masher’s grip. In a rage he lifted her off the floor and growled, “You lousy coke-whore!”

Sabrina wrinkled her nose and spat in his face.

With his captive suspended overhead by a grip under her armpits, the man charged across the floor. Although Roscoe would rather have watched someone else deal with the crisis -- after all, he wasn’t in charge and he had a hangover -- no one among the others present moved. Significantly, he was the one most directly between the couple and where they seemed to him to be heading. Roscoe saw the scene’s heavy as about to throw the heroine through the windows, so he sprang from his seat.

Knowing a half-hearted gesture was likely to make matters worse, Roscoe slammed his right shoulder into the villain’s thighs with utter sincerity. Sabrina was freed as a result of the collision. Riding the momentum of his surge, Roscoe ripped the man’s legs up to drive him onto the tile floor on his back.

As he scrambled to his feet, Roscoe heard Rusty asking the damsel if she was all right. Disheveled and flustered, she grabbed her pocketbook and ran toward the door. She didn’t look back or say, “thanks.” Roscoe let the urge to speak to her pass, as his Sabrina disappeared forever.

Having caught his breath the lout got up from the floor, apologized profusely and slapped a $20 tip on his $12 check. Nonetheless, Rusty made him stay for a few more minutes in an awkward silence, to give the woman a better head start. Then he sent the guy packing with, “Listen here, don’t let me see you in here again. Get it? Don’t come back.”

Sal observed, “That slimy dude better be happy he’s not on his way to jail, or the hospital.”

Rusty picked up a fifth of Bushmills from the back bar. He placed three shot glasses on the bar. He poured, “Scoe, I’m glad you put that sicko in his place.”

Roscoe said, “I couldn’t just sit and watch him throw her through the glass. I had no choice.”

“Wa-a-ait a minute, man,” Sal said. “What makes you so certain that’s what he was going to do?”

As the Eagles’ “Hotel California” began to play, Rusty put in, “Look, either way, he had it coming. That poseur was way, way out of line. I’ve served him in here before, he’s always had a bad attitude.”

“No! It wasn’t like that, Rusty,” resisted Roscoe. “I wasn’t punishing him. They were two or three steps from ... I could see where it was going. Otherwise, it’s none of my business.”

Kit supported Roscoe, “I’m sure that poor woman is very thankful, even…”

“How can you know? pounced Sal. “Nobody else in the saloon felt obliged to nuke the dandy. Then again, the girl was pretty, hmmm, just your type.”

“Hey, my type, too,” jabbed Rusty.

“I heard that!” Peach laughed.

“Wait a minute,” said Roscoe. “The only reason I interfered was because I could see what he was doing ... the look he had ... I couldn’t allow it.”

“Interfered?” Sal mocked. “If that was interfering, I’d hate to see how hard you’d have hit the sucker if you held a grudge. Like, do you know him from somewhere?”

“No,” Roscoe laughed.

Rusty and Sal began rehashing the details of a two-month-old disputed game with their chief softball rival, the Back Door, a nearby bar. Roscoe searched the room for someone to testify on his behalf. Kit was talking to Peach. Once again he caught sight of the Mona Lisa painting on the back wall. For the first time, it seemed funny -- Mona’s mugging expression said it all.

Roscoe looked through the windows again. Pine Street seemed the same, but his hangover had subsided. With that realization he remembered where he had seen the expression in Sabrina’s eyes before. It was the key scene in “La Jette,” a short French New Wave film, which was made up of still images that dissolved, one over another.

Solving the mystery pleased Roscoe. Setting his empty glass down, he declared, “You guys can say what you want. I made a total commitment to my particular view of reality. Maybe I’m crazy, I couldn’t just watch.”

“Amen,” said Rusty. “I don’t care about any hidden motives. Thanks for putting the brakes on whatever was going to happen next.”

“I tell you what, man,” said Sal. “Bake would have said “amen” over that go-for-broke tackle, too. It was solid as a brick!”

“There you go, saving a worthy damsel-in-distress, that’s good karma,” said Rusty. “Who knows…”

“Nobody knows,” said Roscoe with a sardonic smile. “Nobody. Pour us three more, please, on me. Let’s drink to wherever hangovers go and to the utmost of worthy damsels, Rayle’s own cross-eyed Mona.”

* * *

All rights reserved by the author. Cross-eyed Mona, with its accompanying illustration, are part of a series of stories called Detached. Two remaining stories, set in the '70s, will be inserted, eventually. Links to the six others which have been finished are below: