Note: In June of 1984 Richmonders experienced an abrupt change in the way news was gathered and presented. One

monster jailbreak story made that happen. Then I

stumbled onto an offbeat gimmick in the world of self-publishing. This

piece about that episode was first written in 1988 for publication in

SLANT, then I rewrote it in 2005.

Today I have mixed feeling about this episode. Maybe the best thing I can say about it is that I ended up learning more than I bargained for. It certainly proved to me that regardless of the artist's intentions, in the first place, viewers will usually decide for themselves what it means to them ... as I suppose they should.

*

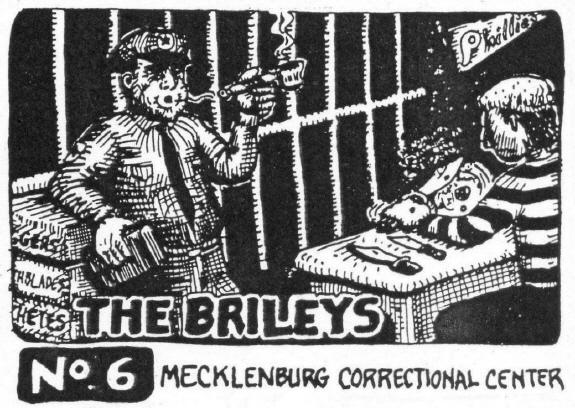

Having terrorized the town with a series of grisly murders five years before, on May 31, 1984, brothers Linwood and James Briley led the largest death-row jailbreak in U.S. history. In all, six condemned men flew the coop by overpowering prison guards, donning the guards’ uniforms and creating a bogus bomb-scare to bamboozle their way out of Virginia’s supposedly escape-proof Mecklenburg Correctional Center.

While their four accomplices were rounded up quickly, the brothers Briley remained at large for 19 days. The FBI captured the duo at a picnic adjacent to the garage where they had found work in Philadelphia.

Linwood was subsequently electrocuted in Richmond on Oct. 12, 1984; likewise, James on Apr. 18, 1985.

While the Brileys were on the run the media coverage, both local and national, was unprecedented. During the manhunt the Brileys-mania led to stories about them being spotted simultaneously in various locations on the East Coast from North Carolina to Canada. When I noticed kids in the Carytown area were pretending to be the Brileys, and playing chasing games accordingly, well, that was just too damn much.

My sense of it then was the depraved were being transformed into celebrities so newspapers and television stations could sell lots of ads. Once they were on the lam, if it came to making a buck, it didn’t seem to matter anymore what the Brileys had done to be on death row.

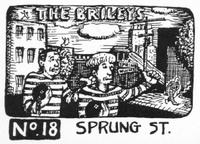

“OK,” I said to a familiar Power Corner group in the Texas-Wisconsin Border Cafe on a mid-June evening, “if the Brileys can be made into heroes to sell tires and sofas on TV, how long will it be before they're on collectable cards, like baseball cards? (or words to that effect).” To illustrate my point I grabbed a couple of those Border logo imprinted cardboard coasters from the bar and sketched quick examples on the backs, which got laughs.

*

Traveling about the Fan District on my bicycle, it took about three days to sell the first press-run out of my olive drab backpack. New cards were designed, more sets were printed, more plastic bags, more bubble gum.

A half-dozen locations began selling “The Brileys” on a

consignment basis. Sales were boosted when the local

press began doing stories on them. For about a week I was

much-interviewed by local reporters and orders to buy card sets began coming in the mail from Europe.

Reporters called me for easy quotes to fill articles on death penalty issues; that I was opposed to the death penalty seemed to strike them as odd. Finding myself in a position to goose a story that was lampooning the overkill presentation of the same press corps that was interviewing me was fun, at first. In the midst of a TV interview I announced that T-shirts commemorating the Brileys' 1984 Summer Tour were on the way.

Apart from my efforts, the hated Briley brothers’ chilling crime spree and subsequent escape inspired all sorts of lowbrow jokes and sick songs, and you-name-it, which did indeed fan the flames of racial hate in Virginia. Naively, I felt no connection to that scene.

Reporters called me for easy quotes to fill articles on death penalty issues; that I was opposed to the death penalty seemed to strike them as odd. Finding myself in a position to goose a story that was lampooning the overkill presentation of the same press corps that was interviewing me was fun, at first. In the midst of a TV interview I announced that T-shirts commemorating the Brileys' 1984 Summer Tour were on the way.

Apart from my efforts, the hated Briley brothers’ chilling crime spree and subsequent escape inspired all sorts of lowbrow jokes and sick songs, and you-name-it, which did indeed fan the flames of racial hate in Virginia. Naively, I felt no connection to that scene.

At least, not until a stop at the silk screen printer’s plant suddenly

cast a new light on the fly-by-night project that summer's effort

was. Walking from the offices to the loading dock meant passing

through a warehouse full of boxes, stacked to the ceiling. Suddenly, I

was surrounded: Four or five young men closed in and cornered me.

Some of them, if not all, had box cutters in their hands; all of them were definitely Black. At that moment I felt Whiter than Ross Mackenzie. Tension filled the air when their spokesman asked if I was the man behind the cards and T-shirts.

As it was not the first time I’d been subjected to questions about the cards, I quickly asked if any of them had seen the cards, or had they only heard about them? As I suspected, they hadn’t seen them.

Luckily, I had a pack in my shirt pocket, which I took out and handed to the group’s leader. As he studied them, one by one, his cohorts looked over his shoulder. I explained what my original motivation had been in creating the cartoons. No one laughed but the spell was soon broken. I let them keep the cards.

Later I was in a

drug store, restocking one of my dealers for the cards, when a White

lady with blue hair approached me. She worked there and had seen the

cards, which she found unfunny. The woman told me her husband was on the

crew that had cleaned up the crime scenes after some of the murders.

Then she said that if I was going to profit from it, I should be man

enough to hear her out.

So, I did. She gave me specific details. It was mostly stuff I had known, or suspected, but the way she told it was brutal.

At this point the success of my absurd art project seemed to be going sour. I got a call from a reporter asking me what I had to say about Linwood Briley having made some disparaging remarks about my cards. I got peeved and asked the scribe what the hell anybody ought to care about what such a man has to say.

Some of them, if not all, had box cutters in their hands; all of them were definitely Black. At that moment I felt Whiter than Ross Mackenzie. Tension filled the air when their spokesman asked if I was the man behind the cards and T-shirts.

As it was not the first time I’d been subjected to questions about the cards, I quickly asked if any of them had seen the cards, or had they only heard about them? As I suspected, they hadn’t seen them.

Luckily, I had a pack in my shirt pocket, which I took out and handed to the group’s leader. As he studied them, one by one, his cohorts looked over his shoulder. I explained what my original motivation had been in creating the cartoons. No one laughed but the spell was soon broken. I let them keep the cards.

So, I did. She gave me specific details. It was mostly stuff I had known, or suspected, but the way she told it was brutal.

At this point the success of my absurd art project seemed to be going sour. I got a call from a reporter asking me what I had to say about Linwood Briley having made some disparaging remarks about my cards. I got peeved and asked the scribe what the hell anybody ought to care about what such a man has to say.

Like it or not, I had become a part of what I had been mocking in the

first place, which I mentioned in an interview with a Washington Post

reporter writing about the phenomenon.

Rea says he designed the cards to deflate what he saw as the growing mythology of the Brileys, and to lampoon what he viewed as excessive media attention to their exploits. "The cards are deliberately provocative," he said. "I sensed that the Brileys, because of their derring-do, were becoming heroes. People wanted to know everything about them. We had two to three articles in the paper every day down here."Rea drew the first cartoons for friends. When they found them amusing, he decided to market them at $1.50 a pack. "I'm a little uncomfortable that I'm becoming a part of the point I'm making," he said.

So I decided to withdraw the cards and T-shirts from the market. Today, without the context of the 1984 news stories being fresh, the humor aspect of the cards is somewhat arcane now. All the

images were based on details from the aforementioned over-reported stories.

About three years later, I was having a beer in the Bamboo Cafe, standing at the bar at Happy Hour talking with friends. A middle-aged man that I didn’t know stepped my way. Furtively, he asked if I was the guy who “drew those Briley cards.”

About three years later, I was having a beer in the Bamboo Cafe, standing at the bar at Happy Hour talking with friends. A middle-aged man that I didn’t know stepped my way. Furtively, he asked if I was the guy who “drew those Briley cards.”

After

I said, “yes,” and introduced myself, he asked me a few frequently asked questions

about the cards. Then he spoke in a hushed tone, saying something

like, “What about those missing cards?”

After

I said, “yes,” and introduced myself, he asked me a few frequently asked questions

about the cards. Then he spoke in a hushed tone, saying something

like, “What about those missing cards?”“Missing cards?” I returned, feeling uncomfortable. “Are you asking why I skipped some numbers?

He nodded and reached in his shirt pocket to pull out a full set of The Brileys, with the cards still in the original plastic bag. Wanting to end the conversation quickly -- that he had the cards with him was way too strange for me -- I told him the simple truth with no jokes: “OK. First, I wanted to imply there was a vast series out there, without having to create it. Then, I wanted the viewer to maybe imagine for himself what the other cards might be.”

The collector put the cards back in his pocket. He stepped away, plainly disappointed with my easy answer, which gave him no dripping red meat to savor. As I remember it, he just stepped away and didn't say anything else ... which was fine with me.

That night in the Bamboo the truth without adornment was of little use to

my public, such as it was.

-- 30 --

No comments:

Post a Comment