To: Richmonders, one and all

Re: The Binding Referendum Project

As 2013 is ending City Hall seems to be telling the citizens of Richmond they have two choices in how they may react to the new baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom deal. We can like it, or we can lump it.

With a slick propaganda campaign pushing this newest version of the baseball in the Bottom plan, the task of stopping City Hall’s bandwagon won’t be easy. Yes, some powerful locals are on the bandwagon. But there are some everyday folks in Richmond who think there may be a way to stop it, using the best tool available in a democracy -- votes.

The first meeting was a step. Held Tuesday evening (Dec. 17) in the old fire station that now houses Gallery 5, it breathed life into the Binding Referendum Project.

Eight people sat down and talked about standing on common ground. They didn’t necessarily agree on the best path to that ground. Some talked more than others but everyone had their say. Views were politely discussed, questions were asked. There were more questions than answers.

The goal of the group -- that common ground thing -- is to stop the building of a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom, and to put an end to such a bad idea. The goal is not to dictate where, or even if, a new baseball stadium will be built.

In the process of the conversation the would-be collaborators seemed to be becoming a little more comfortable with one another. It wasn't a get-together of old friends. It was discussion about a political strategy, devoid of ideology. As the eight left the hour-long confab, as faint as it may have been, there was a spirit of collegiality in the air.

In 2014 this new group expects to add considerably to its numbers. Next month the group plans to propose a feasible solution to the problem those two choices pose. A third choice is being crafted.

As you enjoy the holidays season, there's new hope that the right thing will be done. Hey, who's against democracy?

From: Terry Rea (ftrea9@gmail.com)

Wednesday, December 18, 2013

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Signs of Protest: Photographs from the Civil Rights Era

This press release just came in from Suzanne Hall at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts:

VMFA acquires new works by African American photographers

Bob Adelman, Demonstrator During the March on Washington, D.C., 1963,

printed 2013, gelatin silver print.

Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund.

Aldine S. Hartman Endowment Fund.

Signs and protests were inseparable in the 1960s, with words painted or printed large scale to produce maximum impact when photographed or filmed by the media. Like a visual bullhorn, they both amplified and unified the voices fighting injustice. Ninety percent of the works featured in Signs of Protest: Photographs from the Civil Rights Era were acquired by VMFA in the past three years and emphasize the museum’s commitment to diversifying its photography collection.

On view from January 11 to August 3, 2014, the exhibitions includes photographs that feature protest signs, as well as images of the larger culture of resistance surrounding them, with an emphasis on Civil Rights leaders.

Featured icons of the movement include Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael. Benedict Fernandez’s powerful portfolio, Countdown to Eternity, documents the last year of King’s life. Other images express the need for opposition, such as Gordon Parks’ striking photograph of an aunt and niece standing under the neon sign, “Colored Entrance,” outside a movie theater in Alabama. Likewise, Richard Anderson captured a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Richmond, Virginia, with a “Restaurant Closed” sign prominently advertising the store’s refusal to serve its African American customers.

Featured artists include Benedict Fernandez, Gordon Parks, Louis Draper, Beuford Smith, Leroy Henderson, Bob Adelman, among others. Also included is a photograph by South African photographer Ian Berry of the late South African leader, Nelson Mandela.

Signs of Protest is a part of Race, Place and Identity, a community collaboration of eight institutions presenting work inspired in part by Signs of Protest.

*

Title: Signs of Protest: Photographs from the Civil Rights Era

Date: January 11 – August 3, 2014

Curator: Dr. Sarah Eckhardt, Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

Number of works: Approximately 24

Admission: Free

About the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts:

VMFA’s permanent collection encompasses more than 33,000 works of art spanning 5,000 years of world history. Its collections of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, English silver, Fabergé, and the art of South Asia are among the finest in the nation. With acclaimed holdings in American, British Sporting, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist, and Modern and Contemporary art – and additional strengths in African, Ancient, East Asian, and European – VMFA ranks as one of the top comprehensive art museums in the United States.

Programs include educational activities and studio classes for all ages, plus lively after-hours events. VMFA’s Statewide Partnership program includes traveling exhibitions, artist and teacher workshops, and lectures across the Commonwealth.

VMFA is open 365 days a year and general admission is always free. For additional information, telephone 804-340-1400 or visit www.vmfa.museum.

* * *

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

Re: Mandela

It seems that Nelson Mandela became what his country needed in the 1950s. And, in the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s and especially in the ‘90s. While he called for change, he changed. He became wiser.

Celebrating one of his personal heroes, President Barack Obama praised Nelson Mandela as the last great liberator of the 20th century, urging the world to carry on his legacy by fighting inequality, poverty and discrimination. At a memorial service in Johannesburg, Obama compared the former South African President to Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Lincoln.Click here to read the entire piece from AP at the PBS website.

Furthermore, there's no need to cast him as a saint now, although what he did for peace and freedom once he was released from prison was saintly, indeed.

Today, those pissants who want to pursue their low-road political games within the Republican Party, to mimic what American rightwingers were saying about Mandela 30 or 40 years ago, are revealing more about themselves than they are about the man Obama just eulogized.

Although some people in America have no ability to grasp what "reconciliation" means, most of the world couldn't care less about the Tea Party's political jockeying.

-- Photo by Herman Verwey/Foto24/Gallo Images/Getty Images via AP

Billy Ray Hatley Tribute Concert

The Billy Ray Hatley Tribute Concert was show business at it best: the music was joyful and uplifting. The vibe in the room was inspirational.

From my STYLE Weekly review of the Billy Ray Hatley Tribute Concert at the National on Sunday night:

To read the entire piece click here.

From my STYLE Weekly review of the Billy Ray Hatley Tribute Concert at the National on Sunday night:

Although the stage was filled by 24 performers (with a stage crew of eight), the entertainment offered was no jam session and the show ran smoothly. No covers of rock ’n’ roll classics were played. Every song was written by Billy Ray Hatley, who can no longer perform them. In all, one corny old show biz word well describes how the concert went over -- "boffo!"

To read the entire piece click here.

Sunday, December 08, 2013

Giving Peace a Chance

The first pass at telling this tale appeared in SLANT in 1987.

The version below was updated in 2012.

On the occasion of the anniversary of his death, on Dec. 8, 1980, I can’t help but wonder what the founder of the Beatles — John Lennon, a master of word-play and sarcasm — would have to say about today's music, art and politics.

It would be anybody's guess. After all, in his nearly 20 years as a public figure Lennon’s knack for changing before our eyes was dazzling. There's no reason to think such a restless soul wouldn't have kept on changing.

In November, 2008, on the occasion of what was the 40th anniversary of the release of the Beatles’ White Album, the Vatican newspaper praised the groundbreaking British band for its body of work and forgave Lennon for his flippant 1966 quip about sudden success, “[We’re] more popular than Jesus.”

Even the bloody Vatican has changed but peace is still waiting, off-stage, for its chance.

In February of 1964 the Beatles made their initial appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show. At the time most people probably didn’t connect the events, but those two appearances were less than three months after the assassination of President Kennedy. Surely, the somber mood of the nation, still trying to regain its balance, had something to do with why those fresh sounding Beatles songs cut through the airwaves with such verve.

Clearly, there has been no explosion in the American pop music scene since them, with anything near the equivalent impact of Liverpool’s Fab Four.

Then, in 1980, the murder of moody John Lennon had an impact on the public few would have predicted. It was as if a world leader had been gunned down on the street in Manhattan.

Lennon’s obvious contributions as a songwriter and musician were huge. However, it was the working class hero’s sincerity, his sense of humor and delight in taking risks that helped set him apart from his teen idol counterparts, many of whom toyed with politics and social causes as if they were merely hairdos or dance crazes.

With the Vietnam War still underway in the early ‘70s, President Richard Nixon looked at Lennon and saw the raw power to galvanize a generation’s anti-establishment sentiments. Fearful of that potential, the Nixon administration did everything it could to hound Lennon out of the country. The details of that nasty little campaign are just as bewildering as some of the better known abuses that flowed from the Dirty Tricks Department in the White House during those scandal-ridden days.

With so many years of perspective on Lennon’s death, I have to say that even if that particular nut-case (a man I choose not to name because I refuse to add in any way to his celebrity) hadn’t pulled the trigger, it could easily have been another one; surely there were other bullets out there with John Lennon’s name on them.

Like the comets of each generation are bound to do, sometimes Lennon burned too bright for his own good. And, speaking of assassinations, at this time I’m also reminded of an item that ran in the Nashville Banner on Feb. 24, 1987. The article began with this:

Two Nashville musicians remained free on $500 bond today after they went on a magazine-shredding tear …to protest People magazine’s current cover story.The two musicians were Gregg Wetzel, and Mike McAdam. As members of the Good Humor Band they were fixtures in Richmond’s Rock ‘n’ Roll scene in the early ‘80s. By the time the story mentioned above was published, the pair had established themselves as respected sidemen in Nashville — Wetzel on piano and McAdam on guitar.

In a nutshell, Gregg and Mike became incensed at seeing the magazine with a cover story about John Lennon’s murderer. They felt spotlighting the killer in that way might encourage another deranged wannabe to take gun in hand to go after whoever. So they fortified themselves with an adequate dose of what-it-takes — legend has it they were drinking out of an Elvis decanter — and set out on a mission to destroy the cover of every copy of the offensive publication they could find on the strip.

As the reader may know, this sort of endeavor is frequently best undertaken in the wee hours. In the course of their fifth stop, at a Nashville convenience store, the avenging angels were stopped by the cops and charged with “malicious mischief.”

Shortly afterwards, in a interview about the incident, McAdam said at the time, “If another guy like [name withheld again] sees that, he might think he can get on the cover of People magazine by killing a politician or artist.”

Bravo!

Primary among the reasons John Lennon was selected for the kill by his stalking murderer was he had a rare ability to move people. In that sense, Lennon was slain for the same reason as political figures such as Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy. Two thousand years ago Jesus H. Christ was taken out of the game for much the same reason: He challenged people to change; to take a chance on a life based on something better than might making right.

Although Nixon miscalculated Lennon’s intentions, the soon-to-be-disgraced president was probably right about the former Beatle’s potential to focus the anti-establishment sentiments in the air. What Nixon didn’t grasp was that Lennon — in spite of his mischievous streak — was really more interested in promoting peace than fomenting revolution.

“The cops looked at me and McAdam,” said Wetzel recently, to flesh out the 25-year-old tale, “decided we weren’t exactly flight risks and entrusted our transport to the pokey with an attractive female officer, all by her lonesome. On the way to the hoosegow, Mickey hit on the cop. True story.”

After listening to a John Lennon compilation CD, even today, some of his best post-Beatles cuts seem fresh, they still have the feeling of being experimental.

Well into what are strange days, indeed, 32 years after Lennon's departure from the realm of the living, this grizzled scribbler can smile, wondering what more he would have imagined.

Peace.

-- 30 --

Friday, December 06, 2013

The Billy Ray Hatley Tribute Show

|

| To enlarge the poster art click on it. |

For the Billy Ray Hatley tribute show at The National, among the performers onstage Sun., Dec. 8, (7 p.m. until 10:30 p.m.) will be: Rico Antonelli, Charles Arthur, Steve Bassett, Bill Blue, Craig Evans, Chris Fuller, Susan Greenbaum, Janet Martin, Mike McAdam, Gayle McGehee, Mic Muller, Bruce Olsen, Li’l Ronnie Owens, Velpo Robertson, Robbin Thompson, Brad Tucker, Jim Wark and Chuck Wrenn.

You can't go to the real High on the Hog, anymore. It's history. Same with the Changing of the Seasons party the Usry brothers used to stage every fall. But at the National on Sunday night you can get a nice dose of the spirit and the music that animated those fondly remembered annual get-togethers.

For some background on why this show has been eight months in the planning and rehearsing click here to read Brent Baldwin's "For the Sake of the Song."

Rain or shine, the movie cameras (six of them) in the theater will document what unfolds. And, yes, although it's billed as a concert, there will be an area for dancing.

For more information about this one-of-a-kind gathering of a generation of Richmond-connected musicians and their friends click here to visit the Facebook page for the event.

For more info and to buy tickets go here.

Monday, December 02, 2013

Looting RVA?

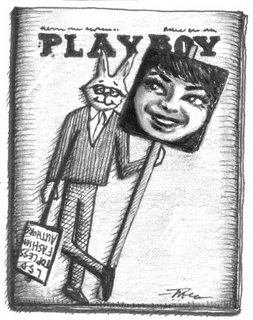

Please feel free to borrow the mockup, if you like, in order to express yourself. For more on this click here to visit the Referendum? Bring It On! Facebook page.

Eating Dandelions, Tasting Freedom

Note: All the food-consciousness and emphasis on thankfulness of the weekend now getting smaller in the rear-view mirror reminded me of a particular connection between those topics that I wrote about 11 years ago. With her appeals exhausted, Beverly Monore began serving her 22-year prison term in 1996. In 2002 a federal judge ordered her immediate release. Then she had to wait for months to see if she would be retried.

Over the year of 2002 I wrote pieces about her plight for three different local periodicals. To read the one I wrote for STYLE Weekly click here. The longest of those articles was the feature published by FiftyPlus. It is below:

Note: Due to space concerns, or perhaps other considerations, The Actual Testimony Sidebar was not run as part of the feature in 2002. So the readers of FiftyPlus didn’t get to see it.

Beverly Monroe was exonerated in 2003 and remains free. That’s something for which I’m sure she remains grateful. Since that turbulent time she and her daughter, Katie, have both become a tireless advocates for the wrongfully convicted. To this day, I’ll bet Beverly can still remember the bitter taste of those dandelions.

Over the year of 2002 I wrote pieces about her plight for three different local periodicals. To read the one I wrote for STYLE Weekly click here. The longest of those articles was the feature published by FiftyPlus. It is below:

Eating Dandelions, Tasting Freedom

by F. T. Rea

On March 5, 1992 Beverly Anne Monroe began to lose her hold on the strands of the life she had known. That morning her boyfriend/companion of more than a decade, Roger Zygmunt de la Burde, 60, was found dead in the library of his house, situated in Powhatan County, on 220 acres along the James River. De la Burde had been shot once in the head; his own handgun was at his side on a couch. County officials acted on the assumption they were dealing with a suicide. Yet, later that same year, Beverly Monroe found herself listening to testimony in support of the charge that she had committed a cold-blooded murder.

The prosecutor, Jack Lewis, told the jury that Monroe had admitted to David Riley, a state police special investigator, she was in the room when the gun went off. Monroe vigorously challenged that assertion, proclaiming her innocence. The defendant left the courtroom facing twenty-two years of incarceration.

After losing appeals in state courts, on April 5, 2002, Monroe was released from prison by order of U.S. District Judge Richard L. Williams. In vacating her conviction, Judge Williams wrote, "This case is a monument to prosecutorial indiscretions and mishandling."

Upon hearing the news she would leave Pocahontas Correctional Unit that day Monroe returned to the stark building in which she had lived, to fetch her belongings.

"In both dorms they [the prisoners] were all pressed against the bars, cheering, screaming to congratulate me," says Monroe. "It wasn’t about me, it was about hope."

*

The original trial wiped out Beverly Monroe’s savings; eventually all she had was liquidated.

"[Then] We sold the house in order to pay for the habeas process," says Katie Monroe, Beverly Monroe’s daughter who is an attorney.

Now 37, in 1996 Katie Monroe set her own career aside, at the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, to work exclusively toward her mother’s release. As she labored with appeals she also established a non-profit group to raise funds and network. And, she put up a web site (www.freebeverly.com) to help disseminate and collect information.

"All in all, this has cost over $500,000, says Katie Monroe."

Beverly Monroe, 64, now lives in Katie Monroe’s cheerful yellow house on a quiet street in Richmond’s Bellevue neighborhood. That setting provides an opportunity for Monroe to pursue her lifelong interest in outdoor activities as she tends the backyard garden there. In prison the presence of wildflowers had lifted her spirits. Weeds capable of growing anywhere, even along the perimeter of razor-wired topped fences, were an inspiration.

Beverly Monroe asserts, as well, that dandelions have nutritional value.

As she received short rations of fruit and vegetables, and she wasn’t keen on the balogna that was readily available, dandelions mattered. "But you don’t eat them for the taste," Monroe says, nodding her head slightly for emphasis.

Beverly Monroe’s chief pleasure, these days, is sharing time with her daughter’s son, Asher, who is four. She’s been teaching him to hit a tennis ball, also how to spell and write.

"There are days I take care of Asher and we play cowboys with stick horses," says the proud grandmother, her blue eyes sparkling.

*

A book on the fascinating Monroe case, "The Count and the Confession," by John Taylor, hit bookstores earlier this year. Both NBC Dateline and a TNT cable television documentary have examined the mysteries of the case. Each of these studies has revealed that Special Agent Riley played an especially aggressive role in converting a situation originally viewed as a suicide into a murder investigation.

Judge Willliams called Riley’s tactics, "deceitful, manipulative, and inappropriate," while finding that the Commonwealth Attorney improperly withheld "exculpatory evidence" - information it had in hand that could favor the defense. His sense of outrage that the prosecutor consistently broke with proper form is plain in the 67 pages of his decision.

Attorney General Jerry Kilgore promptly appealed the Williams decision to the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, a panel of three judges. Briefs have been filed from both sides. On December 3 oral arguments from Monroe’s pro bono legal team - led by Steve Northrup - and the AG’s representatives will begin.

"It feels to me like sheer vindictiveness to keep her in prison," says Northrup. "I don’t understand it."

As for why the commonwealth has moved to set aside Judge Williams’ ruling, Randy Davis, Kilgore’s Deputy Director of Communications says, "It is our duty to protect the citizens of Virginia and continue to pursue violent crime cases. Ten years ago, a jury of her peers from Powhatan County unanimously agreed that Beverly Monroe was guilty of the first degree murder of her lover, Roger de la Burde, and the use of a firearm in the commission of that murder. That conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeals of Virginia and the Supreme Court of Virginia. Since her conviction, 19 judges or justices have reviewed her case. 18 of them, all but one, have concluded she received a fair trial. We have an obligation to the citizens of this Commonwealth to seek judicial review of the ruling of that one judge who has concluded that her trial was not fair."

Katie Monroe says, "The only court to have considered the totality of the prosecutor’s misconduct was the U.S. District Court, which vacated Beverly’s conviction. The majority of the evidence of misconduct was discovered later, after the police and prosecutors were ordered by that court to turn over their files. Neither the Virginia Court of Appeals nor the Virginia Supreme Court considered the impact of what wasn’t seen by the jury. The Attorney General’s reliance on an alleged technicality, to try to reinstate a conviction that was won through prosecutor misconduct, is a disservice to Virginians."

Asked what the appeal is costing taxpayers, Davis responds, "It will cost the same as any other appeal in which we're involved."

*

The daughter of Dallas and Anne Duncan, Beverly Duncan was born in 1938 in Marion, North Carolina. She and her three brothers grew up on a farm in Leeds, South Carolina. In addition to farm chores her father worked for the U.S. Postal Service and her mother was a telegraph operator.

In her teens Beverly Duncan played on the high school basketball team and was named as the prettiest girl in her class. In 1959 she graduated from Limestone College in Gaffney, South Carolina. Then she earned a master’s degree in chemistry from the University of Florida. During her two years in Gainesville she met and married Stuart Monroe, who was working toward his doctorate in chemistry.

After living in Wilmington, Delaware for 3 years the Monroes moved to Ashland, Virginia in 1965; Stuart taught chemistry at Randolph-Macon College, Beverly Monroe stayed at home with her three children while they were young.

In 1970 Dallas Duncan walked into the woods near his home. With a borrowed gun he ended his life. This haunting specter of her father’s suicide returned to play a role in Monroe’s dealing with de la Burde’s violent death.

In 1979 she returned to the workplace; Beverly Monroe accepted a job as a patent researcher at Philip Morris. In 1981 the Monroe’s marriage fell apart, ending in divorce. Beginning again, she built a house in Chesterfield County.

*

At Philip Morris Monroe got to know Roger de la Burde. Eventually they became romantically involved. At the time de la Burde was married. And, as Monroe would eventually learn, he tended to lead a hopelessly complicated life.

Roger de la Burde, a count by his telling, grew up in Poland and came to America in the mid-fifties. Although his scientific work at for Philip Morris was impressive - work from which nine patents flowed - he eventually had a bitter dispute with the company that kept lawyers on both sides of it busy.

"I do know there were times he felt afraid, or even paranoid," says Monroe. "He bought the gun around the time he filed the suit against Philip Morris in about 1987-88, out of some perceived fear. Roger was terribly depressed about the way that was going. He wished he'd never started it."

To gain leverage on the tobacco giant de la Burde is said to have seized some company documents he believed were related to hidden health issues about cigarettes. Shortly after his death that material was carted away by Philip Morris agents, never to surface again.

In published reports after his death de la Burde was remembered by some for his energy and charm. Others saw him as a swindler in business, a fraud in general, and a womanizer. Researchers from all angles seem to agree that his claim to noble ancestry was bogus, as were aspects of his vaunted African art collection.

Katie Monore and her sister, Shannon Monroe, still speak of their fondness for him. Yet, there was a dark and somewhat hidden side to Roger de la Burde. For one thing, he had been taking Librium to help him cope with his anxieties and mood swings and Monroe was completely unaware of that.

Significantly, this information, furnished to the police shortly after his death by his ex-wife, a doctor, was withheld from the defense. This, while the prosecutor built a case on the theory that de la Burde, in spite of his flaws, was an upbeat guy who wouldn’t do himself in.

Beverly Monroe declines opportunities to comment on Burde’s mounting troubles concerning business dealings in real estate or art. She also remains convinced, as do others who were close to him, that he took his life in a fit of depression.

*

As there was little in the way of physical evidence presented, the hinge on which Beverly Monroe’s fate swung in her trial was what she said to David Riley in their conversations - what she said, and why she said it.

To believe Riley’s account and interpretation one must see him as a canny bloodhound that smelled a crime where others had missed it. In a series of meetings set up by Riley, in the weeks after de la Burde’s death, he urged Monroe to accept that a trauma-induced amnesia could have been blocking her memory of that evening; suggesting to her that she was probably present when Burde pulled the trigger. Meanwhile, he didn’t reveal to her that she was being considered as the only real suspect in a murder investigation.

Monroe says she was convinced that Riley, as a professional who knew about such things, was trying to help her. Consequently, she didn’t think to consult an attorney as she discussed trying to recover her supposedly lost memory with Riley. By entertaining the stealth sleuth’s theory of why her grief was so paralyzing in the weeks after de al Burde’s death, Beverly Monroe, herself, unwittingly opened the prison door.

Later, when the commonwealth’s forensic experts testified that de la Burde hadn’t pulled the trigger, the door slammed shut.

Monroe’s motive, the prosecutor told the jury, was jealousy over de al Burde’s other girlfriend, Krystyna Drewnowska, a 40-year-old professor at the Medical College of Virginia, who was pregnant with his child.

Doubting Riley, one might see him as a man who became determined to produce a result that jibed with his first impression as he looked over Polaroids of de la Burde’s body and the position of the gun.

However, what Riley saw as a clue may well have been a bum steer. No one treated the library as a crime scene on March 5, 1992. As the county’s officials examined what they thought to be a suicide, physical evidence was lost. Two Marlboro cigarette butts in an ashtray were thrown away.

Yet, since de la Burde smoked Players and Monroe didn’t smoke, one is left to wonder who may have visited him after Monroe says she left to go home, following their last dinner together.

And, too, the county’s personnel wasn’t overly concerned when the estate’s caretaker, Joe Hairfield - the man who found Burde dead - told deputies that morning he had inadvertently moved the gun as he examined Burde’s body.

As well, Monroe’s forensic experts, who have studied the evidence collected in 1992 since the conviction, insist the commonwealth’s homicide theory is inconsistent with the residues found on Burde’s body, including the presence of primer residue - an invisible chemical that flies out of the back of a gun - found on Burde’s right hand.

*

"I’m going to rebuild my life, we’ve been robbed of it," says Beverly Monroe. "I know it won’t be easy."

Once this ordeal has run its course she wants to continue working in conjunction with others on "wrongful convictions." Without knowing how she will earn a living, she hopes to connect with an established group, or perhaps start her own.

"This has been a ten-year education, I don’t want to waste it," say Monroe.

As she reaches to gather the strands of a new life, Monroe sees her future focus as a matter of righting wrongs. Her sense of solidarity with those who’ve been sprung from prison by post-trial revelations is strong.

"If it happened to me, it can happen to anybody," says Asher’s stick-horse sidekick.

* * *

[Actual Testimony Sidebar]

September 17, 1999: Regarding his tactics during meetings with Monore, Riley’s testimony during a discovery session ordered by Judge Williams was:

"You repeat the theme or modify it slightly, you bob and you weave and commiserate ... And I was very close to her, and ... I wouldn't lose eye contact with her ... I said, we need to work this thing out. And then it didn’t seem like she was willing to accept remembering that she was present or openly remember that maybe she had -- would think of some variation of that such as blocking it from the memory or shock type situation and sometimes it does happen. People are involved in very traumatic situations, the shock is so bad that they really don’t remember the actual event. It’s more like a dream.... I gave her an example of my own father who actually did commit suicide. And I lied to her ... about the fact that I was so shocked that I had blocked it from my memory ... but I was acting with her and doing a darn good job, okay.

"Anyway, she accepted the shock theme. And the thing that really got her to accept it was it was so clear to her that I believed it. It was so clear to me that she believed that I believed people could be shocked to the point where they could block things from their memory. And when I gave her the example of my ... my father’s suicide, that was what seemed to put the cork in it. And so she sort of -- it was sort of like she was in a trance."

December 4, 2001: Beverly Monroe’s testimony about the same at an evidentiary hearing was:

"[Riley] said I know - I know what’s happened. I’ve seen it so many times. He said you have to let me help you with this thing .… But it was going so fast and he was sort of right over me like this and right in my face and it was so loud and nonstop .… He knew I had to have been there. He said this is what he knew had to have happened … and this is what was causing me to have such terrible grief and this was causing me not to be able to remember and that I would never get over it. And that’s truly how I felt; that I would never get over it.

"Riley sounded so knowledgeable and so concerned and so believable … and I had just disintegrated inside from letting this happen to both my father and to Roger. … [Riley] kept trying to put images in my mind by verbalizing what "must have happened" … like my "being asleep on the couch." … He just kept pressing, saying I had to remember .… He was the person in authority and must be right, and I was sure there was something wrong with me because I couldn’t remember."

Note: Due to space concerns, or perhaps other considerations, The Actual Testimony Sidebar was not run as part of the feature in 2002. So the readers of FiftyPlus didn’t get to see it.

Beverly Monroe was exonerated in 2003 and remains free. That’s something for which I’m sure she remains grateful. Since that turbulent time she and her daughter, Katie, have both become a tireless advocates for the wrongfully convicted. To this day, I’ll bet Beverly can still remember the bitter taste of those dandelions.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Fifty years after JFK’s murder it’s time to let sunlight change our ways

Camelot

at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave lasted 1,036 days. For the children in school

on Nov. 22, 1963, the murder of President John F. Kennedy was stunning

in a way nothing has been since. The cynicism the cloaked-in-secrecy

aftermath of the JFK assassination spawned has tinted everything baby

boomers have seen 1963.

Shortly after JFK’s death, in lamenting the demise of Camelot, columnist Mary McGrory said to Daniel Patrick Moynihan: “We’ll never laugh again.”

Moynihan, who was an Assistant Secretary of Labor then, said, “Heavens, Mary, we’ll laugh again. It’s just that we’ll never be young again.”

On Nov. 24, 1963 a live national television audience witnessed the murder of the assassination’s prime suspect, Lee Harvey Oswald. There was no doubt that Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub operator, was the triggerman. What made him do it is still being questioned.

However, please don’t get me wrong. I’m not here to say there had to have been a complicated conspiracy to kill the president and cover up the tracks. After he was dead, just because some people deliberately obscured related information, we don't necessarily know why. In some cases it was probably people trying to cover selected asses for a myriad of reasons.

On the other hand, I’m not saying there was no conspiracy that led up to the murder of President Kennedy. For this 50th anniversary remembrance, I’m skipping past the argument over whether Oswald acted alone. The point to this screed is that the secrecy that surrounded this dark episode poisoned the American culture in a way we need to recognize and think about today.

Tomorrow we need to do something about it.

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known as the Warren Commission, published its report on Sept. 24, 1964: Oswald was found to have been a lone wolf assassin. Which immediately unleashed the questioning of the Commission’s findings. Was its famous “single bullet theory,” which had one projectile traveling circuitously through two victims, great sleuthing?

Or was it an unbelievable reach?

In 1965 gunmen murdered Malcolm X in an auditorium in Manhattan. Three years later Martin Luther King was killed on a motel balcony in Memphis by a sniper. Two months after that assassination Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down in a Los Angeles hotel.

Unfortunately, the official stories on those three shootings were widely disbelieved, too. In the ‘60s more public scrutiny of how those assassination probes were conducted might have led to different conclusions. Even if more sunlight into those probes failed to produce different outcomes, at least Americans might have felt better about the good faith of the processes.

Instead, it seemed then the authorities generally believed the citizenry didn't really have a right to see the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Too often they decided the public was better off not knowing some things, as if we were/are all children. Of course, such secrecy can hide everyday malfeasance, as well.

That sort of thinking is what you can get during wars with spies lucking about. And, in the ‘60s the United States wasn’t just in the scariest part of the Cold War, the culture was very much still in the post-WWII era. Therefore the public had come to expect its government to withhold all sorts of secrets.

It took the rudest of revelations to snap us out of blithely tolerating an over-abundance of secrecy:

Now we know we were wrong to have accepted the lies and cover-ups. Now, in order to trust official conclusions, we must see into the investigations. That means more public hearings. Now for democracy to have a chance of working properly, we need to know whose money is behind this or that politician. We, the people, can’t allow the fundraising and sausage-making to continue to be done in the dark.

Moreover, in 2013, we, the people, have no privacy. Our governments and plenty of large corporations already know all they want to know about us. They monitor our moves as a matter of course. To level the playing field we need more scrutiny of their moves.

In 1997 Sen. Moynihan’s book, “Secrecy: The American Experience,” was published. In the opening chapter he wrote:

Sunlight is THE political issue for 2014. Fifty years after the murder that we baby boomers can still feel in our guts, it’s time to begin sweeping this country’s lumpy accumulation of secret dirt out from under the officially-tacked-down carpets. It's time to say NO to more cover-ups. It’s time to change our ways.

Single bullet theory?

Great name for a band.

Shortly after JFK’s death, in lamenting the demise of Camelot, columnist Mary McGrory said to Daniel Patrick Moynihan: “We’ll never laugh again.”

Moynihan, who was an Assistant Secretary of Labor then, said, “Heavens, Mary, we’ll laugh again. It’s just that we’ll never be young again.”

On Nov. 24, 1963 a live national television audience witnessed the murder of the assassination’s prime suspect, Lee Harvey Oswald. There was no doubt that Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub operator, was the triggerman. What made him do it is still being questioned.

However, please don’t get me wrong. I’m not here to say there had to have been a complicated conspiracy to kill the president and cover up the tracks. After he was dead, just because some people deliberately obscured related information, we don't necessarily know why. In some cases it was probably people trying to cover selected asses for a myriad of reasons.

On the other hand, I’m not saying there was no conspiracy that led up to the murder of President Kennedy. For this 50th anniversary remembrance, I’m skipping past the argument over whether Oswald acted alone. The point to this screed is that the secrecy that surrounded this dark episode poisoned the American culture in a way we need to recognize and think about today.

Tomorrow we need to do something about it.

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known as the Warren Commission, published its report on Sept. 24, 1964: Oswald was found to have been a lone wolf assassin. Which immediately unleashed the questioning of the Commission’s findings. Was its famous “single bullet theory,” which had one projectile traveling circuitously through two victims, great sleuthing?

Or was it an unbelievable reach?

In 1965 gunmen murdered Malcolm X in an auditorium in Manhattan. Three years later Martin Luther King was killed on a motel balcony in Memphis by a sniper. Two months after that assassination Robert F. Kennedy was gunned down in a Los Angeles hotel.

Unfortunately, the official stories on those three shootings were widely disbelieved, too. In the ‘60s more public scrutiny of how those assassination probes were conducted might have led to different conclusions. Even if more sunlight into those probes failed to produce different outcomes, at least Americans might have felt better about the good faith of the processes.

Instead, it seemed then the authorities generally believed the citizenry didn't really have a right to see the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Too often they decided the public was better off not knowing some things, as if we were/are all children. Of course, such secrecy can hide everyday malfeasance, as well.

That sort of thinking is what you can get during wars with spies lucking about. And, in the ‘60s the United States wasn’t just in the scariest part of the Cold War, the culture was very much still in the post-WWII era. Therefore the public had come to expect its government to withhold all sorts of secrets.

It took the rudest of revelations to snap us out of blithely tolerating an over-abundance of secrecy:

- The My Lai Massacre horrors.

- The publishing of the Pentagon Papers.

- The Watergate Scandal hearings.

- The Iran-Contra Scandal hearings.

- The bogus justification for invading Iraq.

Now we know we were wrong to have accepted the lies and cover-ups. Now, in order to trust official conclusions, we must see into the investigations. That means more public hearings. Now for democracy to have a chance of working properly, we need to know whose money is behind this or that politician. We, the people, can’t allow the fundraising and sausage-making to continue to be done in the dark.

Moreover, in 2013, we, the people, have no privacy. Our governments and plenty of large corporations already know all they want to know about us. They monitor our moves as a matter of course. To level the playing field we need more scrutiny of their moves.

In 1997 Sen. Moynihan’s book, “Secrecy: The American Experience,” was published. In the opening chapter he wrote:

In the United States, secrecy is an institution of the administrative state that developed during the great conflicts of the twentieth century. It is distinctive primarily in that it is all but unexamined. There is a formidable literature on regulation of the public mode, virtually none on secrecy. Rather, there is a considerable literature, but it is mostly secret. Indeed, the modes of secrecy remain for the most part--well, secret. On inquiry there are regularities: patterns that fit well enough with what we have learned about other forms of regulation. But there has been so little inquiry that the actors involved seem hardly to know the set roles they play. Most important, they seem never to know the damage they can do. This is something more than inconveniencing to the citizen. At times, in the name of national security, secrecy has put that very security in harm's way.In the C-SPAN video here Sen. Moynihan and a panel discuss the book in 1998.

Sunlight is THE political issue for 2014. Fifty years after the murder that we baby boomers can still feel in our guts, it’s time to begin sweeping this country’s lumpy accumulation of secret dirt out from under the officially-tacked-down carpets. It's time to say NO to more cover-ups. It’s time to change our ways.

Single bullet theory?

Great name for a band.

-- 30 --

Monday, November 18, 2013

The kibosh on baseball in the Bottom

Enough is enough.

In 2005 the shaky plan to build a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom failed. In 2009 another unpopular plan went down in flames. Then, in 2013, the results of a Richmond Times-Dispatch opinion poll said two-thirds of Richmonders are opposed to building a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom.

But we’re told it’s a done deal this time, in spite of the opposition. We’re being told the powers that be have ordained it. Opinion polls can’t stop it.

Well, I want to do more than just complain as City Hall tries to jam its new baseball stadium project down our throats. But ranting under the contents of articles published online about the project won’t stop it. As much as some of us might enjoy it, neither will ranting on Facebook. However, just because it won’t be easy to apply brakes to the wheels of this unholy bandwagon of developers and politicians doesn‘t mean it can‘t be done.

There is a way to do it.

After over 10 years of this controversy flapping in the breeze the politicians on City Council have failed us. According to the law in Virginia, as I read it, there are two ways to get a referendum before Richmond’s voters. One requires the backing of five City Council members. That’s what Second District representative Charles Samuels tried to do in July. His proposal for an “advisory” referendum failed by a 6-3 vote.

The second way involves a petition-signing campaign. It requires a lot of work. But with a team made up of the willing and determined it could be done.

If you are interested in knowing more about how citizens in Richmond can solve this problem themselves -- using a “binding” referendum -- send me an email (ftrea9@gmail.com) or message me on Facebook. We don’t have to give up. With a good plan and some hard work a righteous coalition can put the kibosh on baseball in the Bottom ... for good.

In 2005 the shaky plan to build a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom failed. In 2009 another unpopular plan went down in flames. Then, in 2013, the results of a Richmond Times-Dispatch opinion poll said two-thirds of Richmonders are opposed to building a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom.

But we’re told it’s a done deal this time, in spite of the opposition. We’re being told the powers that be have ordained it. Opinion polls can’t stop it.

Well, I want to do more than just complain as City Hall tries to jam its new baseball stadium project down our throats. But ranting under the contents of articles published online about the project won’t stop it. As much as some of us might enjoy it, neither will ranting on Facebook. However, just because it won’t be easy to apply brakes to the wheels of this unholy bandwagon of developers and politicians doesn‘t mean it can‘t be done.

There is a way to do it.

After over 10 years of this controversy flapping in the breeze the politicians on City Council have failed us. According to the law in Virginia, as I read it, there are two ways to get a referendum before Richmond’s voters. One requires the backing of five City Council members. That’s what Second District representative Charles Samuels tried to do in July. His proposal for an “advisory” referendum failed by a 6-3 vote.

The second way involves a petition-signing campaign. It requires a lot of work. But with a team made up of the willing and determined it could be done.

If you are interested in knowing more about how citizens in Richmond can solve this problem themselves -- using a “binding” referendum -- send me an email (ftrea9@gmail.com) or message me on Facebook. We don’t have to give up. With a good plan and some hard work a righteous coalition can put the kibosh on baseball in the Bottom ... for good.

Friday, November 15, 2013

The Byrd Theatre

Note: Next month the Byrd Theatre will celebrate its 85th birthday. So I'm glad to congratulate the nonprofit foundation that owns and operates it. The Byrd Theatre Foundation took over operation of the theater in 2007.

In 2004 I wrote the brief history of the Byrd that follows for a local tabloid, FiftyPlus.

In 2004 I wrote the brief history of the Byrd that follows for a local tabloid, FiftyPlus.

The Byrd Theatre: 1928 Movie Palace Faces Its Future

by F.T. Rea

The rising water posed a stark threat. Yet, the cliffhanger wasn’t flickering on the Byrd Theatre’s 16-by-36-foot movie screen.

No, the action was down in the depths of the cavernous building at 2908 West Cary Street. There, an underground spring had swollen out of the chamber that routinely contains it and was lapping at the base of a mammoth three-phase blower motor that circulates seasonally conditioned air throughout the building. The pumping system, designed to carry off excess water, wasn’t functioning because the electricity was out.

Hurricane Isabel’s wet fury [in 2003] had unplugged much of Central Virginia and most of Carytown.

Dissolve to a plot-twist a Hollywood producer would cherish: a generator and pump were located at the eleventh hour and the threatening water subsided.

“I can’t imagine what it would have cost to replace that motor,” said Todd Schall-Vess, the Byrd’s general manager, looking back at that time of peril.

The antique movie theater has dodged many such bullets during its 76-year history. Now, the good luck in the Byrd’s future will come by way of a little help from its friends, if it is to continue its remarkable run - which began the night of December 24, 1928.

A registered national landmark since 1979, Richmond’s Byrd Theatre was named after Richmond’s founder, William Byrd. It is one of the last American movie palaces - most of them built in the late 1920s - still in operation as a privately owned cinema. That it remains an independent operation with a single 1,396-seat auditorium makes its longevity all the more noteworthy.

Strikingly, it cost about $900,000 to build the opulent Byrd. Amenities included fountains, frescos, marbled walls, arches adorned with gold leaf, a richly appointed mezzanine, and red, mohair-covered seats. A two-and-a-half ton Czechoslovakian chandelier, suspended over the auditorium by a steel cable, dazzled patrons with thousands of crystals illuminated by hundreds of colored lights.

Four main players established the Byrd Theatre on what was then called Westhampton Avenue. Visionary owners Walter Coulter and Charles Somma set it in motion. They hired Fred Bishop as architect/contractor, as well as the manager, Robert “Bob” Coulter, Walter's brother.

They all had to be optimists. In placing such a plush cinema in a developing area far from the downtown theater district, they took an enormous risk.

The first feature presentation at the Byrd was Waterfront, a light comedy that used the experimental Vitaphone sound system; accompanying 78-rpm records had to be synchronized on the fly. The film starred the vivacious Dorothy Mackaill and elegant leading man Jack Mulhall. The program opened with organist Carl Rond playing “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In the mid-1930s, a change came about. Neighborhood Theatres, owned primarily by real-estate man Morton G. Thalhimer and managed by Sam Bendheim, Jr., assumed the running of the Byrd. Neighborhood was then in the process of establishing itself as the region’s dominant chain. With Bob Coulter staying on as manger, the Byrd served as the flagship of the Richmond-based chain’s operation until 1970, when it opened the Ridge Twin Cinemas in Henrico County.

A 1952 Richmond News Leader article on the history of Richmond’s movie theaters, written by George Rogers, offered, “Robert Coulter at the Byrd is the dean of managers.”

As late as the 1960s ordinary people still routinely dressed up to go to the movies. An evening’s show at the Byrd would include a newsreel, a cartoon, a comedy or travelogue, and a live set by the ever-popular Eddie Weaver at the Mighty Wurlitzer.

Rising up from a dark pit before the screen, Weaver worked furiously at the pipe organ’s console. By pushing various buttons, keys, and pedals, the maestro could also play a harp, a piano, drums and more - real instruments, some of them visible to the audience, up in the wings.

After a short set of rousing tunes, Weaver would descend back into the pit. Then, from the projection booth, the sweet chattering sound of one of two heavy-geared 35mm movie projectors could be heard pulling a leader through its gate. Presto! The ancient carbon-arc lamp would project a stream of light through the moving celluloid strip, and an image would burst onto the screen.

Today, the Byrd uses that same pair of 1953 Simplex projectors.

Weaver’s regular performances at the Byrd spanned twenty years, from 1961 to 1981. For the last seven years Bob Gulledge has been sitting on what was Weaver’s bench.

As for Coulter, he retired in 1971, at age 76, and died in 1978 - although according to his 2004 counterpart, Schall-Vess, a ghostly presence said to resemble Coulter has been spotted over the years, sitting in what had been his favorite chair on the cantilevered balcony.

In the 1960s and 1970s America’s cities saw unprecedented growth in their suburbs. New multi-screened theaters began popping up like mushrooms in shopping centers. More screens under one roof meant expanded customer options. In the process, single-screen houses without parking lots gradually lost their leverage with movie distributors.

That process undermined urban cinemas everywhere. The list of darkened screens within Richmond’s city limits over the last three decades includes evocative names such as the Biograph, the Booker T, the Brookland, the Capitol, the Colonial, the Edison, the Loew’s, and the Towne.

Into the mid-1970s the Byrd continued to exhibit first-run pictures. With business falling off, the region’s distributors eventually decided it was no longer worthy of commanding exclusive runs of the most sought-after titles. By 1983 Sam Bendheim III, who by then was managing the Neighborhood chain, could no longer justify keeping the Byrd open. As well, Samuel Warren bought the building.

To the rescue came Duane Nelson, an assistant manager in the Byrd’s last days under Neighborhood’s auspices. Unable to bear the thought of the screen going dark, Nelson, who had studied the development of historical properties at VCU, lined up a partner: Jerry Cable, creator of the Tobacco Company, in some ways the most significant restaurant in Shockoe Slip since the late-1970s. Together, in 1984, Nelson and Cable secured a lease and set about revitalizing the West Cary Street anachronism.

For five years they struggled with little success to establish the theater as a repertory house, facing the booking and film-shipping nightmares posed by offering a steady diet of double features for short runs. Recognizing that changes had to be made, the partners eventually parted ways, and the Byrd has been under Nelson’s leadership ever since.

Nelson’s role in shielding the Byrd from the wrecking ball, or from being converted into a flea market or some other less-than-appropriate use, is commendable. Over the last fourteen years his policy has been to offer bargain-priced, second-run features. And this strategy has resulted in a certain measure of stability.

Film-rental fees come out of box-office receipts in the form of a percentage; distributors generally take between forty and seventy percent. Consequently, most movie theaters, including the Byrd, lean heavily on revenue from their concession stands. On the other hand, by showing second-run movies the Byrd is not obliged to charge its customers the steep price of admission that distributors insist upon for first-run releases.

The $1.99 ticket scheme works as long as the crowds are large enough to buy plenty of popcorn. Because of the traffic this formula brings to the area, Nelson’s fellow Carytown retailers are smiling about the Byrd’s customary long lines.

The Nelson formula also includes special events. Live Christmas shows have featured high-kicking chorus lines, and every spring the VCU French Film Festival takes over the Byrd for three days. More than 16,000 tickets were sold for the 2003 series, which the French government formally recognized as the largest French film festival in the United States.

As Nelson sees it, the city itself provides some of the most frustrating obstacles for the Byrd. “We’re competing against [multiplexes in] the counties. Richmond’s theaters pay a twenty-five-percent utilities tax, a six-percent food tax, and a seven-percent admissions tax that they don’t have to pay.”

Nelson has company. Without exception, Richmond’s entertainment-industry veterans decry the seven-percent grab - off-the-top - that the city demands from ticket sales.

Still, the show goes on. And if the Byrd’s survival is to be assured well into the 21st century, it will probably be due to the efforts of people like Bertie Selvey and Tony Pelling.

Selvey was a longtime supporter of TheatreVirginia, the live stage formerly in operation at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (1955-2002). And now she is a driving force behind the Byrd Watchers, a group of volunteers that she founded to raise money for preserving the theater.

“I need a cause,” explained Selvey. “The Byrd is an endangered species.”

Why endangered? As Nelson admits, although the Byrd has been taking in sufficient revenue to stay afloat on a day-to-day basis, putting away reserves to restore the building properly - or perhaps withstand the next hurricane - remain out of reach. In recent years the current owners of the property, heirs to the Warren estate, have been quite flexible in their rental demands. But clearly, something needs to be done. Recognizing the seriousness of the situation, Nelson seems ready to pass the torch.

Rather than wait for a crisis, a group of supporters has devised a plan to secure the Byrd’s future. It calls for the theater to be operated by a not-for-profit foundation, thus putting it in a position to accept broader community support and to take advantage of some attractive tax advantages.

Accordingly, the Byrd Theatre Foundation was established. Its aim is to purchase the property and to assume responsibility for the theater’s management. Pelling, a retired Under Secretary from the UK Civil Service, assumed the role of the Foundation’s president, a volunteer task, in January of this year. Although he and Selvey have had little experience in the art of selling movies to the public, in truth, they join a long list of important players in Richmond’s movie-theater history who had little in the way of credentials before taking the plunge.

In 1928 posh movie palaces opened in cities coast-to-coast. Most have not survived. As it has before, Richmond’s Byrd Theatre has somehow managed to imbue its current stewards and a growing list of civic-minded contributors with enough of that same Roaring ‘20s optimism to keep the light on the screen.

[sidebar]

A Grand Plan for the Byrd

The Byrd Theatre Foundation intends to purchase the Byrd Theatre. The ultimate goal is to restore the theater to its original splendor and to operate it much as it has been in recent years: playing popular fare, mostly as a second-run discount house. The price tag on that dream is $3.5 million.

The Foundation has its 501(C)(3) status, which means that donations are tax deductible. Once the theater is purchased, it will be owned and operated by the Foundation.

Immediate needs include a new roof, refurbished seats, new carpeting, repair of the Mighty Wurlitzer organ, and a thorough cleaning. It is also hoped that the 1930s neon marquee will be restored. The estimated cost of these projects is $2.5 million.

[sidebar]

Movie Theater Mania

There are records of an exhibition of “moving pictures” presented at The Academy (originally called the Mozart Academy of Music) at 103-05 N. Eighth Street in 1897. Built in 1886, that venue was generally considered to be Richmond’s most important and stylish theater - until it burned down in 1927. It is said that in 1906 the Idlewood Amusement Park held regular screenings of “photo dramas.”

However, one showman, Jake Wells, has been credited with being “a theatrical proprietor, impresario and father of Richmond movie houses” (according to George W. Rogers, writing in the Richmond News Leader in 1952). Wells was a former-major league baseball player (1882-84), who had served as the manager of the city’s entry in the Atlantic League during the Gay Nineties.

In 1899 Wells opened the Bijou, on the northeast corner of 7th and Broad Streets. Offering family-oriented fare, the venue thrived. Encouraged by his success, Wells began to expand his influence. With his younger brother, Otto, he opened the Granby Theatre in Norfolk in 1901. Eventually they built a chain of forty-two theaters throughout the Southeast. A second version of the Bijou was built for Wells in 1905 at 816 East Broad, on the site of the legendary Swan Tavern.

By the early 1920s the feature-length movie had been established by Hollywood as a cash cow. Theaters were being built that were designed to be cinemas primarily, rather than multipurpose stages. America was caught in a veritable explosion of popular culture. The influence of national magazines was at an unprecedented level and commercial radio was booming. It was the Roaring ‘20s, and more theaters were needed.

The Byrd Theatre and the Loew’s (now the Carpenter Center) both opened in 1928. Most of their counterparts, styled after grand European opera houses, were also built just before the Depression. Coincidentally, at the same time talkies were revolutionizing the movie business.

The next thrilling episode of the Byrd’s story calls for a cast of thousands to stoke the wonder of the theater that puts the “town” in Carytown.

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

VCU outlasts UVA

Tuesday night in Charlottesville VCU defeated Virginia at the sold-out JPJ Center: VCU 59, UVA 56.

College basketball games played before Thanksgiving Day can look half-baked. Frequently coaches are still tinkering with their lineups. Even teams blessed with plenty of good players can look sloppy or lackluster. And, although the Cavs and the Rams will surely play more artistic games later in this season, they both brought an intensity to the floor that looked like mid-season form.

Both UVA (No. 25 AP Poll) and VCU (No. 14 AP Poll) are already formidable teams and they treated a national television audience to a pretty decent game. Because it was a tilt dominated by the defenses, some armchair coaches will criticize the quality of the performances. I'd rather watch paint dry than listen to much of that kind of talk.

Yes, both teams missed too many free throws. The refs slowed the game down by calling 48 fouls, which was too many. But as hard as the two teams were playing, I'm sure the guys on the court were grateful to catch a breath.

The Cavs committed 19 turnovers, while making just 18 field goals. While that's not a winning formula they offset that woeful statistical comparison by dominating the glass; Virginia pulled down 40 rebounds to VCU‘s 24.

UVA needs to be able to hit a few jump shots. VCU's slashers need to kick the ball back out sometimes. All that will probably come with a few more games.

The winning shot (shown in the video), a 30-footer by Treveon Graham, broke a tie with just one second left in the game. Graham led all scorers with 22 points.

Click here to see the box score.

Tuesday, November 12, 2013

Referendum on baseball stadium?

Mayor Dwight Jones obviously knows how to please certain developers and businessmen. Maybe he knows how to steamroll members of City Council, too.

Q: What does Jones know about baseball?

A: At one of the 2008 mayoral debates I covered, I heard Jones say Richmond should forget about the minor leagues and hold out for a major league team to move here. Most of the people in the room who knew how silly and revealing that statement was managed not to laugh out loud. Some couldn't help it.

Q: Will the same six members of Council who voted against the referendum four months ago now support the mayor’s new plan for baseball in the Bottom?

A: Well, in July, if they already knew they were going to support the developers' plan, it's easy to see why the same six wouldn't want a referendum revealing how much Richmonders oppose it.

Q: Is there a way for citizens to go around City Council to have a referendum, anyway?

A: It isn’t easy but the answer is, yes!

Q: Short of a referendum underlining the collective will of the people, is there much chance of stopping this project?

Monday, November 11, 2013

Who's Afraid of a Referendum?

From the Richmond Times-Dispatch:

To read the entire story, "Shockoe Bottom plan draws protesters," click here.

Last summer City Council voted 6-3 against allowing for a referendum on whether to build a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom. Although the controversy is over 10 years old, some said they needed to see a specific proposal.

Now they have it.

So, perhaps if two more Council members decide it's time to let the voters have a say, then everyone will be able to see the truth about what Richmonders want. Which politicians on City Council feel answerable to what the tax payers want to do with the baseball stadium question remains to be seen.

For some background click here to read "When Allies can't work together" at SLANTblog.

Click here to visit the Facebook page for "Referendum? Bring It On!

Mayor Dwight Jones was heckled by protesters during this morning's announcement of a $200 million Shockoe Bottom development that will include a new minor league baseball park.

The downtown ballpark has been criticized for its potential impact on a nearby slave burial ground and the history of the slave trade in the Bottom.

Jones said proponents of the project need to listen to the critics.

To read the entire story, "Shockoe Bottom plan draws protesters," click here.

Last summer City Council voted 6-3 against allowing for a referendum on whether to build a baseball stadium in Shockoe Bottom. Although the controversy is over 10 years old, some said they needed to see a specific proposal.

Now they have it.

So, perhaps if two more Council members decide it's time to let the voters have a say, then everyone will be able to see the truth about what Richmonders want. Which politicians on City Council feel answerable to what the tax payers want to do with the baseball stadium question remains to be seen.

For some background click here to read "When Allies can't work together" at SLANTblog.

Click here to visit the Facebook page for "Referendum? Bring It On!

Central Time

Fiction by F. T. Rea

Fiction by F. T. ReaAugust 16, 1966: Roscoe Swift sat alone in a day car slowly rattling its way into Central Station. The solitary sailor had spent the last hour turning the glossy pages of Playboy and contemplating infinity. As the train lurched he glanced out of the window at Tuesday morning, Chicago style.

Roscoe had sequestered himself from the marathon poker game in another car. The further the train had gotten from Main Street Station in Richmond the more the call for wild cards and split pots had grown. Finally it had driven him from the table. His resolute grandfather had schooled him to avoid such frilly variations on the already-perfect game of poker.

“Gimmicks like that were invented to keep suckers in the game,” was the old man’s admonition.

On the way to boot camp, volunteering to be a sucker seemed like a bad idea. This was hardly the day Roscoe wanted to invite the jinx that might be set loose by disrespecting absolutes.

In the magazine’s lengthy interview section LSD pioneer Timothy Leary ruminated on his chemically enlarged view of the so-called Youth Movement. Professor Leary called the baby boomers, “The wisest and holiest generation that the human race has yet seen.”

The subculture forming around psychedelic drugs in that time was opening new dimensions of risk for 19-year-old daredevils. Roscoe wondered if he would ever do acid. His friend Bake had tripped and lived to tell about it.

There was a fresh dimension to the conflict in Vietnam that month. The Cold War’s hottest spot was being infused with its first batch of draftees; some 65,000 were being sent into the fray. Until this point it had been the Defense Department’s policy to use volunteers only for combat duty.

On the home-front quakes in the culture were also abundant: A 25-year-old former Eagle Scout, Charles Whitman, climbed a tower on the University of Texas campus and shot 46 people, at random, killing 16; comedian/first amendment martyr Lenny Bruce was found dead -- overdosed and fat belly up -- on his bathroom floor; news of songwriter/musician John Lennon’s playful crack about his band -- “We’re more popular than Jesus Christ now” -- inflamed the devoutly humorless; and reigning Heavyweight Champ, Muhammad Ali, bent all sorts of folks out of shape with his widely reported quip -- “I ain't got nothing against them Viet Cong.”

Since leaving Virginia the morning before, Roscoe had traveled -- via the Chesapeake and Ohio line -- through parts of West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana, on his way to Illinois.

Taking leave from the airbrushed charms of a model billed as Diane Chandler, who was September’s Playmate of the Month, his mind kaleidoscoped to an image of another smiling pretty girl, Julie, his girlfriend.

Then, for a second, Roscoe could feel the sound of Julie's laughter.

As a preamble to Roscoe’s departure for basic training he and Julie had spent the weekend in Virginia Beach, trying their best to savor the bittersweet taste of war-torn romance, black and white movie style. As luck would have it, the stately Cavalier Hotel’s central air conditioning system went on the blink the Friday they arrived.

Since the hotel’s windows couldn't be opened that meant the sea breeze was unavailable for relief from the heat wave. Nonetheless, they stayed on, because the hotel itself, a stylish relic of the Roaring ‘20s, meant something. After two years of catch-as-catch-can back-seat romance, this was where they had chosen to spend their first whole night together.

That evening they stretched out on the bed and sipped chilled champagne. With the hotel-supplied fan blowing on them at full blast, suddenly, a good-sized chunk of the ceiling fell onto a chair across the room.

Roscoe reported the strange problem to the front desk, “I hate to sound like Chicken Little, but perhaps you have a safer room?”

Then Julie suggested a stroll on the beach to cool off. Walking barefoot in the surf, neither of them had much to say. An hour later Julie and Roscoe were back at the hotel. With a little snooping around the pair discovered the door to the Cavalier’s indoor pool was unlocked. As it was well past the posted time for the pool to be open and the lights were off in the chlorine-smelling room, they reasoned the facility was at their disposal for a little skinny-dipping.

Roscoe set the magazine aside and smiled, thinking of the adage about how Richmond girls are always wilder at the Beach.

*

Stepping off the train, Roscoe was two hours from another train ride. This one, aboard a local commuter, would finish the job of transporting him from Richmond’s Fan District -- with its turn-of-the-century townhouses -- to a stark world of colorless buildings and punishing paved grinders: Great Lakes Naval Training Center was his destination.

In the last month Roscoe had listened to plenty of supposedly useful yarns of what to expect at boot camp. Concerning Chicago, he could recite facts about the White Sox, the Cubs and the Bears; he had seen the movie about Mrs. O’Leary’s cow and the big fire; he thought Bo Diddley was from Chicago. One thing was certain, Seaman Recruit Swift knew he was further from home than he’d ever been.

Outside the train station on the sidewalk, “They’re Coming to Take Me Away” -- a novelty tune on the summer's Top 40 chart -- blared appropriately from the radio of a double-parked Pontiac GTO.

After laughing at the ironic coincidence of the music, Roscoe, Zach, Rusty, and Cliff - comrades-at-arms in the same Navy Reserve unit in Richmond for four months of weekly meetings - considered their options for killing the time between trains, and they spoke of the ordeal ahead of them.

“That’s it, man.” Rusty explained. “The Navy figures everybody eats Jell-O, so that’s where they slip you the dose of saltpeter.”

“Get serious, that’s got to be bullshit,” said Zach. “The old salts tell you that to jerk you around.”

“OK, Zach, you can have all my Jell-O,” Rusty offered.

“Not even a breeze; what do y’all make of the Windy City?” asked Cliff. “It’s just as damn hot up here as it was in Richmond.”

A couple of blocks from the station the team of eastern time-zoners, outfitted in their summer whites, stopped on a busy corner to scan the hazy urban landscape. Finding a worthwhile sightseeing adventure was at the top of their agenda.

Answering the call, a rumpled character slowly approached the quartet from across the street. Moving with a purpose, he was a journeyman wino who knew a soft touch when he could focus on it.

In a vaguely European accent the street-wise operator badgered the four out of a cigarette, a light, two more cigarettes for later, then a contribution of spare change. When the foul-smelling panhandler demanded “folding money” Roscoe turned from the scene and walked away. His pals followed his lead. Then the crew broke into a sprint to escape the sound of the greedy beggar’s shouts.

Rusty, the fastest afoot, darted into a subway entrance with the others at his heels. Cliff was laughing so hard he slipped on the steps and almost fell.

As Roscoe descended the stairway into the netherworld beneath the city, he was reminded of H. G. Wells’ “Time Machine” and observed, “I guess this must be where the Morlocks of the Midway would live; if there are any.”

Zach smiled. No one laughed.

The squad agreed that since they were already there, and only Rusty had ever seen a subway, a little reconnoitering was in order. Thus they bought tokens, planning only to look around, not to ride. Roscoe, the last to go through the turnstile, wandered off on his own to inspect the mysterious tracks that disappeared into darkness.

Standing close to the platform’s edge, Roscoe wondered how tightly the trains fit into the channel. As he listened to his friends’ soft accents ricocheting off the hard surfaces of the deserted subway stop, he recalled a trip by train in 1955’s summer with his grandfather. Roscoe smiled as he thought of his lifelong fascination with trains. Unlike most of his traveling companions, he was glad the airline strike had forced them to make the journey by rail.

Walking aimlessly along the platform, as he reminisced, Roscoe noticed a distant silhouette furtively approaching the edge. It appeared to him to be a small woman. She was less than a hundred yards down the tracks. He watched her sit down carefully on the platform. She didn't move like a young woman. Seconds later she slid off, disappearing into the dark pit below.

Although Roscoe was intrigued, he felt no sense of alarm. Not yet.

Rosacoe didn’t wonder if it was a common practice for the natives to jump onto the subway tracks. He simply continued to walk toward the scene, slowly taking it in, as if it were a movie. When Zach caught up with him Roscoe pointed to where the enigmatic figure had been.

Roscoe shrugged, “What do you make of it?”

"Let's see where she went," Zach said.

To investigate the two walked closer. Eventually they saw a gray lump on the subway tracks. It hardly looked like a person. Then they heard what was surely the sound of an approaching train coming out of the tunnel’s void.

As Roscoe shouted at the woman to get up, Zach took off in the direction of the sound of the train. The scene took on a high-contrast, film noir look when the tunnel was suddenly lit up by the train’s light.

Running toward the train, the two desperate sailors waved their arms frantically to get someone’s attention. As they sprinted past the woman on the tracks she remained clenched into a tight ball, ready to take the big ride.

The subway's brakes began to screech horrifically, splitting seconds into shards.

The woman didn't move.

Metal strained against metal as the train’s momentum continued to carry it forth.

Roscoe's senses were stretched to new limits. Tiny details, angles of light and bits of sound, became magnified. All seemed caught in a spell of slow motion and exaggerated intensity.

The subway train slid to a full stop about ten feet short of creating a grisly finish.

Roscoe and Zach sprang from the platform and gathered the trembling woman from the tracks. They carefully passed her up to Rusty and Cliff, who stood three feet above. Passengers emptied from the train. Adrenaline surged through Roscoe’s limbs as he climbed back onto the platform. Brushing off his uniform, he strained to listen to the conversation between the train's driver and the strange person who had just been a lump on the subway track.

The gray woman, who appeared to be middle-aged, spewed, "Thank you," over and over again. She explained her presence on the tracks to having, “Slipped.”

Shortly later the subway driver acted as if he believed her useful explanation. Zach pulled him aside to say that we had seen the woman jump, not fall, from the platform. Roscoe began to protest to the buzzing mob’s deaf ears, but he stopped abruptly when he detected a feminine voice describing what sounded like a similar incident. He panned the congregation until he found the speaker. She was about his age.

Filing her fingernails with an emery board -- eyes fixed on her work -- she told how another person, a man, had been killed at that same stop last week: “The lady is entitled to die if she wants to. You know she’ll just do it again.”

As she looked up to inspect her audience, such as it was, Roscoe caught Miss Perfect Fingernails’ eye. He shook his head to say, “No!”

The impatient girl looked away and gestured toward the desperate woman who surely had expected to be conning St. Peter at the Pearly Gates that morning, instead of a subway driver. “Now we’re late for our appointments. For what?”

Roscoe watched the forsaken lady -- snatched from the Grim Reaper’s clutches -- vanish into the ether of the moment’s cheerless confusion. Shortly thereafter the train was gone, too.

“Well, I don’t know about you boys,” said Roscoe. “But I’ve had enough of Chicago sights for today.”

On their way back to daylight Roscoe listened to his longtime friend Zach tell the other two, who were relatively new friends, a story about Bake: To win a bet, Bake, a consummate daredevil, had recently jumped from Richmond’s Huguenot Bridge into the Kanawha Canal.

“Sure sounds like this Bake is a piece of work,” said Cliff. “You said he’s going to RPI this fall. What’s he doing about the draft?”

“This is a guy who believes in spontaneity like it’s sacred,” said Zach. “Roscoe, can you imagine Bake in any branch of military service, draft or no draft?”