|

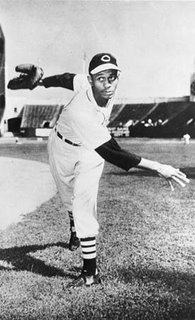

| Satchel Paige in 1949 |

Each spring, with the return of Major League Baseball, naturally, I think of times spent at what was a temple of baseball in my youth, Parker Field. It was located where the Diamond is now on Arthur Ashe Boulevard.

In 1954 Parker Field became the baseball park to serve as the home field for a new International League club — the Richmond Virginians. When the Baltimore Orioles (formerly the St. Louis Browns) joined the American League that year, it created an opening in the IL for the Richmond entry.

A couple of years later, via a business agreement, the V’s became one of the New York Yankees’ Triple A farm clubs. As such, in those days the Bronx Bombers paid Richmond an annual visit in April, just before the Big Leagues' opening day. That meant Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford and the other great Yankees of that era played a preseason exhibition game in Richmond facing the V’s. It was always a standing-room affair.

Today I wish I hadn't lost track off the photos I shot of a few of those Yankees stars at one of those games. When the game ended I hopped over a low wall, to get on the playing field with my Brownie Hawkeye in hand. Before I was shooed away, I did manage to fire off a few semi-closeups.

Other than the pinstripe-clad hometown V’s, my favorite club in the IL in those days was the pre-revolution Havana Sugar Kings. With a single every one of them would round first base like they were going to second. They played with a striking intensity, bordering on reckless abandon. It made them a lot of fun to watch, especially for the kids who played baseball and appreciated that style.

One of my all-time favorites I saw perform on that ball field was Leroy “Satchel” Paige (1906-'82). Yes, the legendary Paige, with his windmill windup, high kick and remarkably smooth release still working for him, actually plied his craft on the mound here in Richmond. I don't remember how many appearances he had here, but I suppose this piece is probably based on a composite of two or three times he pitched.

In 1971, Paige (pictured above, circa 1949) was the first of the legendary Negro Leagues’ stars to be admitted to Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame. His induction was based mostly on his contributions to baseball before he helped break the color line in 1948, as a 42-year-old rookie.

The statistics from Paige's pre-Big League days are mind-boggling. It's been said he won some 2,000 games and threw as many as 45 no-hitters. Furthermore, well before the impish boxer/poet Muhammad Ali, there was the equally playful Satchel Paige, with his famous Six Guidelines to Success:

- Avoid fried meats that angry up the blood.

- If your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts.

- Keep the juices flowing by jangling gently as you walk.

- Go very lightly on the vices, such as carrying-on in society - the society ramble ain’t restful.

- Avoid running at all times.

- Don’t look back, something may be gaining on you.

Long after his days as the best pitcher in the Negro Leagues (maybe any league), and following his precedent-setting stint in the American League, Paige was on the roster of the Miami Marlins (1956-58). Like the V’s, the Marlins played in the International League. When I saw him, Paige was in his 50s (his date of birth was vague). Not a starter, anymore, he worked out of the bullpen.

In the late-1950s live professional baseball in Richmond was mostly a White guys’ scene. Unfortunately, that meant the chorus of boos would start as soon as some in the crowd noticed Paige’s 6-foot-3, 180-pound frame warming up in the middle of a game. When he’d be summonsed to pitch, in relief, the noise level would ratchet up. Not all the grown men booed, but many did. That, while their children and grandchildren were split between booing, cheering, or perhaps being embarrassed and not knowing what to do.

Naturally, some of the kids (like me) liked seeing the grownups getting unraveled, so Paige was all the more cool to us. Sadly, for plenty of White men in Richmond, then caught up by the thinking that buoyed Massive Resistance, any prominent Black person was seen as a figure to be against. So, those booing Paige probably would have booed Duke Ellington or A. Philip Randolph, too.

|

| Paige with two Marlins teammates. |

Upon being called in, the showman Paige would take forever to walk to the mound from the bullpen. Each of his warm-up pitches would be a big production. After a slow motion windup, the ball would whistle toward home plate with a startling velocity, making some of the kids cheer and laugh ... to mix with the boos. Everything Paige did seemed to prompt a reaction from the grandstands.

With his worldwide travels, Paige, from Mobile, Alabama, must have understood what was going on better than most who watched him pitch in the twilight of his career. He knew perfectly well there wasn’t much he could do to change the minds of those who were booing; those folks were trapped in the past.

So, Paige played to the cheers, as his vast experience as a performer had surely taught him to do. Of course, as a 10-year-old I lacked the overview to understand that what I was seeing was an awkward but long overdue change, to do with race, the South was beginning to go through. Much more of that was on the way and some of those booing were probably protesting that, too, in their way.

Nonetheless, my guess is few in attendance grasped that the crowd's mixed reaction to Paige, largely being split on generational lines, was foreshadowing of how America’s baseball fans, coast-to-coast, were going to be changing. One day Jim Crow attitudes would have no proper place at baseball temples.

Now, with the benefit of decades of reflection, I understand that Satchel Paige was a visionary. At Parker Field, Paige was seeing the future by following his own advice -- "Don’t look back."

-- 30 --

-- Images from satchelpage.com

No comments:

Post a Comment