|

A scan of the campaign handbill

mentioned

in this story.

|

Ed. Note: A longer version of this story was published in 1987

in SLANT. Then, in 2000, it was cut down to this version, which ran in STYLE Weekly as a Back Page.

*

In

the spring of 1984, I ran for public office. In case the Rea for City

Council campaign doesn’t ring a bell, it was a spontaneous and totally

independent undertaking. No doubt, it showed. Predictably, I lost, but

I’ve never regretted the snap decision to run, because the education was

well worth the price.

In

truth, I had been mired in a blue funk for some time prior to my

letting a couple of friends, Bill Kitchen and Rocko Yates, talk me into

running, as we played a foozball game in Rockitz, Kitchen's nightclub.

Although I knew winning such an election was out of my reach, I relished

the opportunity to have some fun mocking the system. Besides, at the

time, I needed an adventure.

So

it began. Walking door to door through Richmond’s 5th District,

collecting signatures to qualify to be on the ballot, I talked with

hundreds of people. During that process my attitude about the endeavor

began to expand. People were patting me on the back and saying they

admired my pluck. Of course, what I was not considering was how many

people will encourage a fool to do almost anything that breaks the

monotony.

By

the time I announced my candidacy at a press conference on the steps of

the city library, I was thoroughly enjoying my new role. My confidence

and enthusiasm were compounding daily.

On

a warm April afternoon I was in Gilpin Court stapling handbills,

featuring my smiling face, onto utility poles. Prior to the campaign, I

had never been in Gilpin Court. I had known it only as “the projects.”

Several

small children took to tagging along. Perhaps it was their first view

of a semi-manic white guy — working their turf alone — wearing a

loosened tie, rolled-up shirtsleeves, and khaki pants.

After

their giggling was done, a few of them offered to help out. So, I gave

them fliers and they ran off to dish out my propaganda with a spirit

only children have.

Later

I stopped to watch some older boys playing basketball at the

playground. As I was then an unapologetic hoops junkie, it wasn’t long

before I felt the urge to join them. I played for about 10 minutes, and

amazingly, I held my own.

After

hitting four or five jumpers, I banked in a left-handed runner. It was

bliss, I was in the zone. But I knew enough to quit fast, before the

odds evened out.

Picking

up my staple gun and campaign literature, I felt like a Kennedyesque

messiah, out in the mean streets with the poor kids. Running for office

was a gas; hit a string of jump shots and the world’s bloody grudges and

bad luck will simply melt into the hot asphalt.

A

half-hour later the glamour of politics had worn thin for my troop of

volunteers. Finally, it was down to one boy of about 12 who told me he

carried the newspaper on that street. As he passed the fliers out, I

continued attaching them to poles.

The

two of us went on like that for a good while. As we worked from block

to block he had very little to say. It wasn’t that he was sullen; he was

purposeful and stoic. As we finished the last section to cover, I asked

him a question that had gone over well with children in other parts of

town.

“What’s the best thing and the worst thing about your neighborhood?” I said with faux curiosity.

He stopped. He stared right through me. Although I felt uncomfortable about it, I repeated the question.

When he replied, his tone revealed absolutely no emotion. “Ain’t no best thing … the worst thing is the sound.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, already feeling a chill starting between my shoulder blades.

“The

sound at night, outside my window. The fights, the gunshots, the

screams. I hate it. I try not to listen,” he said, putting his hands

over his ears to show me what he meant.

Stunned,

I looked away to gather my ricocheting thoughts. Hoping for a clue that

would steady me, I asked, “Why are you helping me today?”

He

pointed up at one of my handbills on a pole and replied in his

monotone. “I never met anybody important before. Maybe if you win, you

could change it.”

Words

failed me. Yet I was desperate to say anything that might validate his

hope. Instead, we both stared silently into the afternoon’s long

shadows. Finally, I thanked him for his help. He took extra handbills

and rode off on his bike.

As

I drove across the bridge over the highway that sequesters his stark

neighborhood from through traffic, my eyes burned and my chin quivered

like my grandfather’s used to when he watched a sad movie.

Remembering

being 12 years old and trying to hide my fear behind a hard-rock

expression, I wanted to go back and tell the kid, “Hey, don’t believe in

guys passing out handbills. Don’t fall for anybody’s slogans. Watch

your back and get out of the ghetto as fast as you can.”

But

then I wanted to say, “You’re right! Work hard, be tough, you can

change your neighborhood. You can change the world. Never give up!”

During the ride home to the Fan District, I swore to myself to do my

absolute best to win the election.

A

few weeks later, at what was billed as my victory party, I, too, tried

to be stoic as the telling election results tumbled in. The incumbent

carried six of the district’s seven precincts. I carried one. The total

vote wasn’t even close. Although I felt like I’d been in a car wreck, I

did my best to act nonchalant.

|

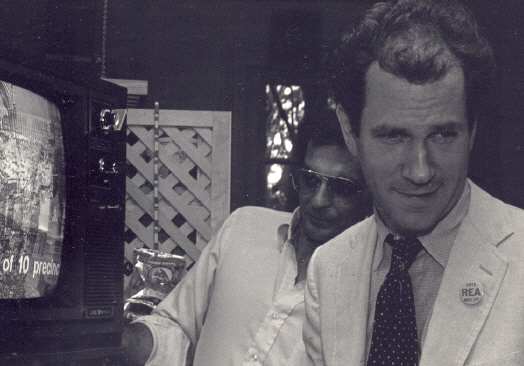

This shot, taken at Grace

Place, shows my reaction to

the news that with half

the votes counted I no longer

had any chance to win. |

In

the course of my travels these days, I sometimes hear Happy Hour wags

laughing off Richmond’s routine murder statistics. They scoff when I

suggest that maybe there are just too many guns about; I’m told that as

long as “we” stay out of “their” neighborhood, there is little to fear.

But

remembering that brave Gilpin Court newspaper boy, I know that to him

the sound of a drug dealer dying in the street was just as terrifying as

the sound of any other human being giving up the ghost.

If

he's still alive, that same boy would be older than I was when I met

him. The ordeal he endured in his childhood was not unlike what children

growing up in any number of the world’s bloody war zones are going

through today. Plenty of them must cover their ears at night, too.

For

the reader who can’t figure out how this story could eventually come to

bear on their own life, then just wait … keep listening.

-- 30 --

No comments:

Post a Comment