|

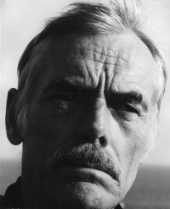

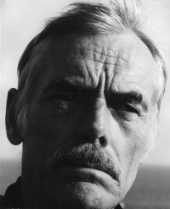

| Balcomb Greene |

Revved up over an English class

assignment to write a paper on "The Second Coming," by W. B. Yeats, I

stayed up all night crafting it, and thought I had hit a home run.

The professor, an awkward, gangly sort of fellow in his late-20s,

gave me a “C” on it.

Well, I just had to ask him to explain to

me what was wrong with the paper. In a private conference he told me

my analysis of the poem didn't jibe with the accepted school of

thought on what Yeats was saying. While admitting my writing and

analytical technique were fine, he nervously explained that I was

simply wrong in my conclusions, no matter how well-stated my case

might have been.

That sort of pissed me off, so I told him I

thought that ambiguity could imply multiple meanings, and it

deliberately invited alternative interpretations. Rather than defend

as his stance the man suddenly grabbed his face and broke into tears.

The

sobbing professor went into a monologue on the shambles his life had

fallen into. His personal life! Worst of all, he said, his deferral

had just been denied by Selective Service, so he would soon be

drafted.

He was wearing a pitiful brown suit. His thinning

beige hair was oiled flat against his scalp. My anger over the bad

grade turned into disgust. As I

remember it, I walked out of his office to keep from telling him what

I thought.

Now, four decades later, I regret my impatience

and feel sorry for the poor schlemiel. Still, when the offer came at

the end of the semester to expand my part-time job to full-time, I

took the leap. My chief duty was to schlep visiting scholars around

Virginia from one university campus to the next in a big black

Lincoln.

Each week, under the auspices of the University

Center in Virginia -- a consortium of Virginia colleges and

universities -- there was a new scholar in a different field.

Somebody had to drive them to lectures, dinners, convocations and to

hotels throughout the week. For one whole semester that was me.

Naturally,

in the crisscrossing of Virginia, the wiseguy driver and the

actually wise scholars had a lot of time to talk. Some of them kept

to themselves, mostly. Others were quite chatty, in several cases we

got along well and had great talks.

Three of them stand out

as having been the best company on the road: Daniel Callahan

(then-writer/editor at Commonweal Magazine), Henry D. Aiken

(writer/philosophy professor) and Balcomb Greene (artist/philosopher

and art history professor).

Callahan

challenged me to think more thoroughly about situational ethics and

morality. He was happy I was reading the books of Herman Hesse and

others. He turned me on to “One Dimensional Man,” by Herbert Marcuse.

Callahan was quite curious about my experiences taking LSD, we talked about drugs and religion. Click

here to read about him.

Aiken

(1912-‘82) was then the chairman of the philosophy department at

Brandeis University, he loved a debate. He was used to holding his own

against the likes of William F. Buckley. Talking with him about

everything under the sun in the wee hours, I first acquired a taste

for good Scotch whiskey (which I haven't tasted in many a year).

From

a ‘pragmatic’ point of view, political philosophy is a monster, and

whenever it has been taken seriously, the consequence, almost

invariably, has been revolution, war, and eventually, the police

state.

-- Henry D. Aiken

Aiken,

like Callahan, agreed to help me with a project I told them about.

Inspired by popular new magazines Ramparts, Avant-Garde, Rolling

Stone, etc. -- at 21-years-old -- I wanted to jump straight into

magazine publishing, with no experience, ASAP.

That dream

stayed on the back burner for 16 years, until the first issue of

SLANT came out in 1985. How I went about designing SLANT to be a small magazine, mostly featuring the work of its publisher, flowed in great part from my brief association with Balcomb Greene (1904-90). Of the rent-a-scholars I met, he was easily the funniest.

The son of a

Methodist minister, Greene grew up in small towns in the Midwest.

He studied philosophy at Syracuse University, psychology at the

University of Vienna and English at Columbia University. Then he

switched to art, having been influenced by his first wife, Gertrude

Glass, an artist he had married in 1926. He became a founder of the

avant-garde group known as American Abstract Artists in 1936.

After

World War II, just as abstract art was gaining acceptance, Greene

radically changed his style. He began painting in a more figurative,

yet dreamy, style that fractured time. Click

here,

and

here, to read about Greene and see examples of his work.

One

day I’ll write a piece about the visit to Sweetbriar with Greene.

It was a hoot collaborating with him, to have some fun putting on

the blue-haired art ladies of that venerable institution. This time

my mention of him is to get this piece to I.F. Stone. It was Greene

who gave me a subscription to I.F. Stone’s Weekly.

I.F.

“Izzy” Stone (1907-89) was an independent journalist in a way few

have ever been. In the 1960s his weekly newsletter was a powerful

voice challenging the government’s propaganda about the war in

Vietnam. Click

here to read about Stone, and

here.

"All governments lie, but disaster lies in wait for countries whose officials smoke the same hashish they give out."

-- I.F. Stone

Stone

remains one of my heroes. At my best, over the years, I have

emulated him in my own small ways. Thank you for the schooling,

Professor Greene.

-- 30 --