Photographer Jack Leigh (1948-2004) was part of the

Biograph Theatre’s staff in late-1973/early-1974 (I managed the place in those days). While he worked at the

Biograph as an usher, Leigh taught me to play Half-Rubber, a game he

said came from his home town, Savannah. Half-Rubber is a three-man

baseball-like game that is played with a broom handle and half of a red

rubber ball.

Probably Jack’s best known photograph was snapped in 1993, when he shot the photo in a Savannah cemetery that would appear on the cover of what became a bestselling book -- “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” by John Berendt. Later the same image was used to promote the movie with the same title.

When

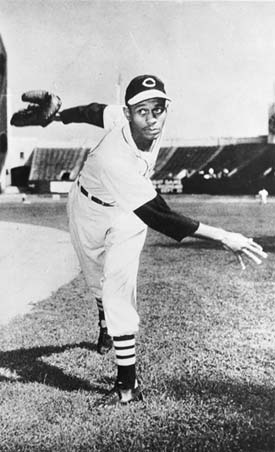

I knew him, Jack (pictured right) was earnest and quick-witted. He liked to play chess

and talk about movies, and of course -- photography. In his Biograph

days he was already a very good photographer. At one point we had a show of his hanging in the lobby.

When

I knew him, Jack (pictured right) was earnest and quick-witted. He liked to play chess

and talk about movies, and of course -- photography. In his Biograph

days he was already a very good photographer. At one point we had a show of his hanging in the lobby.

Once, when we went out to wander around shooting pictures together, he snapped his shutter maybe twice. He was using slow black and white film. Maybe Verichrome Pan? In the same amount of time, a couple of hours, I went through a couple of rolls of fast Tri-X.

Yes, the quiet style Jack would use throughout his career was already evident. He eventually authored six books of photographs, including "Oystering," which featured a foreword by James Dickey.

Back to Half-Rubber: To kill time one pleasant afternoon, at Jack's prompting I cut a ball in half, cut the sweeping part off of a broomstick and crossed the street with the Half-Rubber instructor and the theater’s assistant manager, Bernie Hall. At the time there were a couple of vacant lots on Grace Street, across from the Biograph. With the alley behind us, it was a good spot to play the new game.

Berine and I soon learned the key to pitching was to throw the half-ball using a side-arm delivery, with the flat part down. That made it curve wildly and soar, somewhat like a Frisbee. Hitting it with a broomstick or even catching the damn thing was quite another matter. Oh, and hitting the ball on a bounce was OK, too. In fact, it was better to do so, from a strategic standpoint.

The

pitcher threw the half-sphere in the general direction of the batter. If

the batter swung and missed, and he usually did miss, the catcher did

his best to catch it. When the catcher did

catch it on the fly, providing the batter had swung, the batter was out. Then the

pitcher moved to the catching position, and the catcher became the

batter, and so forth. Runs were scored in a similar fashion to other

home run derby-like games.

The

pitcher threw the half-sphere in the general direction of the batter. If

the batter swung and missed, and he usually did miss, the catcher did

his best to catch it. When the catcher did

catch it on the fly, providing the batter had swung, the batter was out. Then the

pitcher moved to the catching position, and the catcher became the

batter, and so forth. Runs were scored in a similar fashion to other

home run derby-like games.

But the best reason to play, other than the laughs stemming from how foolish we looked dealing with the crazy, flat-sided ball, was the kick that came from hitting it. When we connected with that little red devil it left the broomstick bat like a rocket. Smashing it across the lot, completely over the theater and halfway to Broad Street was a gas!

Click here to read more about Jack Leigh.

Probably Jack’s best known photograph was snapped in 1993, when he shot the photo in a Savannah cemetery that would appear on the cover of what became a bestselling book -- “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” by John Berendt. Later the same image was used to promote the movie with the same title.

When

I knew him, Jack (pictured right) was earnest and quick-witted. He liked to play chess

and talk about movies, and of course -- photography. In his Biograph

days he was already a very good photographer. At one point we had a show of his hanging in the lobby.

When

I knew him, Jack (pictured right) was earnest and quick-witted. He liked to play chess

and talk about movies, and of course -- photography. In his Biograph

days he was already a very good photographer. At one point we had a show of his hanging in the lobby. Once, when we went out to wander around shooting pictures together, he snapped his shutter maybe twice. He was using slow black and white film. Maybe Verichrome Pan? In the same amount of time, a couple of hours, I went through a couple of rolls of fast Tri-X.

Yes, the quiet style Jack would use throughout his career was already evident. He eventually authored six books of photographs, including "Oystering," which featured a foreword by James Dickey.

Back to Half-Rubber: To kill time one pleasant afternoon, at Jack's prompting I cut a ball in half, cut the sweeping part off of a broomstick and crossed the street with the Half-Rubber instructor and the theater’s assistant manager, Bernie Hall. At the time there were a couple of vacant lots on Grace Street, across from the Biograph. With the alley behind us, it was a good spot to play the new game.

Berine and I soon learned the key to pitching was to throw the half-ball using a side-arm delivery, with the flat part down. That made it curve wildly and soar, somewhat like a Frisbee. Hitting it with a broomstick or even catching the damn thing was quite another matter. Oh, and hitting the ball on a bounce was OK, too. In fact, it was better to do so, from a strategic standpoint.

The

pitcher threw the half-sphere in the general direction of the batter. If

the batter swung and missed, and he usually did miss, the catcher did

his best to catch it. When the catcher did

catch it on the fly, providing the batter had swung, the batter was out. Then the

pitcher moved to the catching position, and the catcher became the

batter, and so forth. Runs were scored in a similar fashion to other

home run derby-like games.

The

pitcher threw the half-sphere in the general direction of the batter. If

the batter swung and missed, and he usually did miss, the catcher did

his best to catch it. When the catcher did

catch it on the fly, providing the batter had swung, the batter was out. Then the

pitcher moved to the catching position, and the catcher became the

batter, and so forth. Runs were scored in a similar fashion to other

home run derby-like games.But the best reason to play, other than the laughs stemming from how foolish we looked dealing with the crazy, flat-sided ball, was the kick that came from hitting it. When we connected with that little red devil it left the broomstick bat like a rocket. Smashing it across the lot, completely over the theater and halfway to Broad Street was a gas!

Click here to read more about Jack Leigh.