With another baseball season upon us, I can't help but think of what was a temple of baseball in my youth -- Parker Field, which was located where The Diamond is now. This time of year usually brings to mind some of the players I saw there.

With another baseball season upon us, I can't help but think of what was a temple of baseball in my youth -- Parker Field, which was located where The Diamond is now. This time of year usually brings to mind some of the players I saw there.One of my all-time favorites was Leroy “Satchel” Paige (1906-82). Yep, I actually saw the legendary Paige perform here in Richmond, with his windmill windup, high kick and remarkably smooth release.

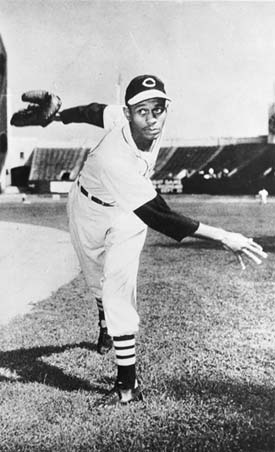

In 1971, Paige (pictured right, circa 1949) was the first of the Negro Leagues’ stars to be admitted to Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame, based mostly on his contributions before he helped break the Major League color line in 1948, as a 42-year-old rookie. The statistics from his pre-Big League days are mind-boggling. Some say he won about 2,000 games and threw maybe 45 no-hitters.

Furthermore, long before the impish poet/boxer Muhammad Ali, there was the equally playful Satchel Paige, with his widely reported Six Guidelines to Success:

- Avoid fried meats that angry up the blood.

- If your stomach disputes you, lie down and pacify it with cool thoughts.

- Keep the juices flowing by jangling gently as you walk.

- Go very lightly on the vices, such as carrying-on in society - the society ramble ain't restful.

- Avoid running at all times.

- Don't look back, something may be gaining on you.

Watching professional baseball in Richmond was mostly a white scene in the late-1950s. The boos would start as soon as the Parker Field crowd noticed Paige’s 6-3, 180-pound frame warming up in the middle of a game. When he’d be called in to pitch in relief, the noise level would soar. Not all the men booed, but many did. That, while their children and grandchildren were split between booing, cheering or not knowing what to do.

Naturally, some of the kids liked to seeing the old goats get pissed off, so Paige was cool to them.

Yet, for many white adults in Richmond, then caught up by the thinking that buoyed Massive Resistance, any prominent black person was seen as someone to be against. So, they probably would have booed Nat King Cole or Duke Ellington, too.

Paige would take forever to walk to the mound from the bullpen. His warm-up pitches would be a big production, with various slow-motion full windups. Then the thrown ball whistled toward home plate with blinding speed, and lots of the kids cheered and laughed.

At the time I hadn’t the slightest idea that what I was seeing was an aspect of the changes the South was going through, to do with race, with the reaction to Paige being split on generational lines. Paige, of course, knew very well he was in the South. Being from Mobile, Alabama, he knew what was going on. He was a consummate performer, who knew there wasn’t much he could do to change the boos; they were coming from folks trapped in the past.

So, Paige good-naturedly played to the cheers, and ignoring the boos, just as he always had.

Now I understand that Satchel Paige was seeing the future, because he followed his own advice -- Don't look back.

-- 30 --

Image from satchelpage.com

Image from satchelpage.com

No comments:

Post a Comment